At the $3.65 poverty line, India accounts for 40% of the slight upward revision of the global poverty rate from 23.6% to 24.1%, according to the World Bank September 2023 Global Poverty Update. It is the same update that made the following recent headline in the Indian and Pakistani media about Pakistan: "Pakistan's 40% Population Lives Below Poverty Line, Says World Bank". Fact: 45.9% of Indians and 39.4% of Pakistanis live below the $3.65 a day poverty line as of September, 2023, according to the the latest World Bank global poverty update that takes into account the impact of inflation on poverty rates. But neither the Pakistani media nor India's compliant "Godi Media" reported it. Nor did they question why poverty in India is growing despite the Modi government's claim to be "the world's fastest growing economy".

|

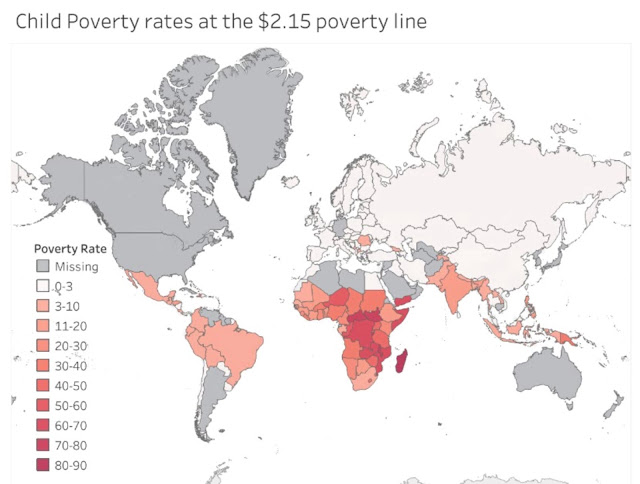

| Global Child Poverty Rate. Source: UNICEF |

Another recent report by UNICEF that went unnoticed by the media is that the child poverty rate in India far exceeds the rate in Bangladesh and Pakistan: At $2.15 poverty level, India has 11.5% children under poverty, Pakistan 5.6% and Bangladesh 5.1%. At $3.65 poverty level, India has 49.8% children under poverty, Pakistan 45% and Bangladesh 35.2%.

|

| Child Poverty Rate By Year By Region From 2013 to 2022. Source: UNICEF |

The UNICEF data shows that the South Asia region's child poverty rate at $2.15 for any year since 2013 drops to about a half when India is excluded.

The latest World Bank and UNICEF reports remind me of the famous Indian writer and poet Javed Akhtar who told his audience at a conference in Mumbai earlier this year that he saw "no visible poverty" in Lahore during his multiple visits to Pakistan over the last three decades. Responding to Indian novelist Chetan Bhagat's query about Pakistan's economic crisis at ABP's "Ideas of India Summit 2023" in Mumbai, Akhtar said: "Unlike what you see in Delhi and

Mumbai, I did not see any visible poverty in Lahore". This was Akhtar's first interview upon his return to India after attending "Faiz Festival" in Lahore, Pakistan.

|

| Javed Akhtar at ABP Ideas Summit in Mumbai |

Chetan Bhagat began by talking about high inflation, low forex reserves and major economic crisis in Pakistan and followed it up by asking Javed Akhtar about its effects he saw on the people in Pakistan. In response, Akhtar said, "Bilkul Nahin (Not at all). In India you see poverty right in front of you, next door to a billionaire. Maybe it is kept back of the beyond. Only some people are allowed to enter certain areas. But you don't see it (poverty) on the streets. In India, it is right in front of you...amiri bhi or gharibi bhi (wealth and poverty). Sare kam apke samne hain (It's all in front of you). Wahan yeh dekhai nahin deta (you don't see it in Pakistan)".

|

| Alhamra Arts Center, Lahore, Pakistan |

Disappointed by the response, Bhagat suggested that the Indian visitor could have been guided by his hosts through certain routes where he couldn't see any poverty. Javed Akhtar then said "it's not possible to hide poverty. I would have seen at least a "jhalak" (glimpse) of it as I always do in Delhi and Mumbai....I have been to Pakistan many times but I have not seen it".

What Javed Akhtar saw and reported recently is obviously anecdotal evidence. But it is also supported by hard data. Over 75% of the world's poor deprived of basic living standards (nutrition, cooking fuel, sanitation and housing) live in India compared to 4.6% in Bangladesh and 4.1% in Pakistan, according to a recently released OPHI/UNDP report on multidimensional poverty. Here's what the report says: "More than 45.5 million poor people are deprived in only these four indicators (nutrition, cooking fuel, sanitation and housing). Of those people, 34.4 million live in India, 2.1 million in Bangladesh and 1.9 million in Pakistan—making this a predominantly South Asian profile".

|

| Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2022. Source: OPHI/UNDP |

|

| Income Poverty in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: Our World in Data |

The UNDP poverty report shows that the income poverty (people living on $1.90 or less per day) in Pakistan is 3.6% while it is 22.5% in India and 14.3% in Bangladesh. In terms of the population vulnerable to multidimensional poverty, Pakistan (12.9%) does better than Bangladesh (18.2%) and India (18.7%) However, Pakistan fares worse than India and Bangladesh in multiple dimensions of poverty. The headline multidimensional poverty (MPI) figure for Pakistan (0.198) is worse than for Bangladesh (0.104) and India (0.069). This is primarily due to the education and health deficits in Pakistan. Adults with fewer than 6 years of schooling are considered multidimensionally poor by OPHI/UNDP. Income poverty is not included in the MPI calculations. The data used by OHP/UNDP for MPI calculation is from years 2017/18 for Pakistan and from years 2019/2021 for India.

|

| Multidimensional Poverty in South Asia. Source: UNDP |

The Indian government's reported multidimensional poverty rate of 25.01% is much higher than the OPHI/UNDP estimate of 16.4%. NITI Ayog report released in November 2021 says: "India’s national MPI identifies 25.01 percent of the population as multidimensionally poor".

|

| Multidimensional Poverty in India. Source: NITI Ayog via IIP |

Earlier last year, Global Hunger Index 2022 reported that India ranks 107th for hunger among 121 nations. The nation fares worse than all of its South Asian neighbors except for war-torn Afghanistan ranked 109, according to the the report. Sri Lanka ranks 64, Nepal 81, Bangladesh 84 and Pakistan 99. India and Pakistan have levels of hunger that are considered serious. Both have slipped on the hunger charts from 2021 when India was ranked 101 and Pakistan 92. Seventeen countries, including Bosnia, China, Kuwait, Turkey and UAE, are collectively ranked between 1 and 17 for having a score of less than five.

Here's a video of Javed Akhtar's interview with Chetan Bhagat at ABP's "Ideas of India Summit 2023". Please watch from 4:19 to 6:00 minutes.

https://www.youtube.com/live/pZ5e81ysKGQ?feature=share

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

India in Crisis: Unemployment and Hunger Persist After COVID

India Rising, Pakistan Collapsing

Record Number of Indians Seeking Asylum in US

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Pakistanis Consuming More Calories, Fruits & Vegetables Per Capita

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

11 comments:

India has had high poverty statistics for long both by numbers and by percentages. It is nothing new. And yet for an economy of its size, its macro-economic indicators are stable, its economy has stable growth (even if not exceptional), inflows of foreign investement is strong, and its forex reserves are at a comfortable level and growing. Yes, India does face long term "challenges" with regard to poverty alleviation, infrastructure and human resource development. But there are no signs of an economic "crisis" at present and no one forsee one in the making as well (atleast for the immediate future).

On the other hand, neighbouring Pakistan has been in the grips of an acute economic crisis - falling industrial production, exports, foreign investor confidence and investment, low forex reserves and very high inflation across the board, which experts fear are signs of a "stagflation" that Pakistan will find difficult to get out of. That is, unless govt dares to make the radical, long-overdue reforms that would inevitably involve pain in the short-term. But so far, successive government strategies appear to have been to borrow more money to fulfill immediate needs and pay back interests on previous debts, and pass the buck to the next government. No reforms are in sight. Pakistan is in a state of crisis that India faced back in 1991, but seems to lack the will to fix the basics and create a foundation for a stable growth. (All I have said here comes from my years of reading DAWN, not any "Godi" Indian media.)

Why is it that I see too few articles about Pakistan's acute economic crisis, since this blog is supposed to be about "South Asia"? Or is the huge numbers of India-centric articles here essentially an acknowledgement of the reality that India is the engine of economic growth in the South Asian region, and that what affects India affects the regional economy as a whole?

New Delhi: A study by the World Bank has concluded that nearly 80% of people who slipped into poverty in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic hailed from India. Out of 7 crore people globally who became poor that year due to economic losses caused by the pandemic, Indians accounted for 5.6 crore.

https://thewire.in/economy/indians-account-for-80-of-those-who-became-poor-globally-in-2020-due-to-covid-19-world-bank

Globally, extreme poverty levels went up to 9.3% in 2020 compared to 8.4% in 2019, halting the progress made by poverty alleviation programmes worldwide for the first time in decades. In absolute numbers, 7 crore people were additionally pushed into extreme poverty by the end of 2020, increasing the global total of poor to over and above 70 crore.

“The COVID-19 pandemic dealt the biggest setback to global poverty in decades,” the World Bank’s Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022: Correcting the Course report declared.

Given that India contributes significantly to global poverty levels due to the sheer size of its population, the World Bank flagged that the lack of official data on poverty from India had become a hindrance in drawing up global estimates. Since 2011, the Indian government has stopped publishing data on poverty.

It noted that due to the lack of official data, the World Bank had relied upon the findings of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s (CMIE’s) Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS).

Although the findings by the private data firm are yet to be finalised, the World Bank said it had used it for estimating Indian, regional and global poverty levels due to the want of official data. The CPHS data for 2020 noted that 5.6 crore Indians slipped into poverty in 2020.

The report said the World Bank chose to use CHPS data for India over its own paper – published in April 2022 and estimated that 2.3 crore Indians additionally slipped into poverty in 2020 – because poverty in India was “significantly higher” than its own estimates.

The confusion over the data emerging from India, as enunciated by the World Bank report, has once again brought to the fore collective frustration and concern articulated by economists and statisticians in the country and the world over for some time now over Narendra Modi’s government reluctance to release official data, adversely affecting developmental interventions.

The most recent official data on poverty in India dates back to 2011-12 by the National Sample Survey Office of India.

The World Bank report, however, noted that depending upon the method of estimating the number of poor in India rose anywhere between 2.3 crore and 5.6 crore in 2020. “A national accounts-based projection implies an increase of 23 million, whereas initial estimates using the data described in box O.2 [relating to CMIE data] suggest an increase of 56 million — this latter number is used for the global estimate,” the report stressed.

“Because of India’s size, the lack of recent survey data for the country significantly affects the measurement of global poverty, as was evident in Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020,” the report said.

The World Bank, however, observed that overall poverty in India was on a downward slide – largely due to a reduction in poverty in rural areas – between 2011 and 2020 when the pandemic hit. “Even though overall poverty has declined, it is by less than what earlier estimates used for global poverty measurement would suggest,” the report noted, referring to the 2011-20 period.

Mr . Vineeth

You said :

————————-

India has had high poverty statistics for long both by numbers and by percentages. It is nothing new. And yet for an economy of its size, its macro-economic indicators are stable, its economy has stable growth (even if not exceptional), inflows of foreign investement is strong, and its forex reserves are at a comfortable level and growing. Yes, India does face long term "challenges" with regard to poverty alleviation, infrastructure and human resource development. But there are no signs of an economic "crisis" at present and no one forsee one in the making as well (atleast for the immediate future).

——————

My comment :

Sir the economy of India has performed really well over some decades as reported by Indian media but the question arises that if it is true then why not enough jobs are being produced in India ?

Pls note Indians claim that India receives more foreign investment than Pakistan and other neighbouring countries which is I think true to some or great extent but Sir the question arises where does that investment go ?

Why inspite of receiving so much investment from other countries and from foreign based companies , still their is huge shortage and crisis of jobs in India ?

STATISTICS !

MEANINHGLESS IN HINDOOSTHAN !

THE CRUX !

EXPLOITATION !

2000 YEARS AGO IT WAS THE BRAHMIJNS AND KSHATRIYAS !

TODAY IT IS THE BANIAS

I QUOTE BR AMBEDKAR IN PAGE 4357 of Selected Works of Dr BR Ambedkar

The Bania is the worst parasitic class known to history. In him the vice of money-making is unredeemed by culture or conscience. He is like an undertaker who prospers when there is an epidemic. The only difference between the undertaker and the Bania is that the undertaker does not create an epidemic while the Bania does. He does not use his money for productive purposes. He uses it to create poverty and more poverty by lending money for unproductive purposes. He lives on interest and as he is told by his religion that money-lending is the occupation prescribed to him by the divine Manu, he looks upon money-lending as both right and righteous. With the help and assistance of the Brahmin judge who is ready to decree his suits, the Bania is able to carry on his trade with the greatest ease. Interest, interest on interest, he adds on and on, and thereby draws millions of families perpetually into his net. Pay him as much as he may, the debtor is always in debt. With no conscience to check him there is no fraud, and there is no chicanery which he will not commit. His grip over

the nation is complete. The whole of poor, starving, illiterate India is irredeemably mortgaged to the Bania.

In every country there is a governing class. No country is free from it. But is there anywhere in the world a governing class with such selfish, diseased and dangerous and perverse mentality, with such a hideous and infamous philosophy of life which advocates the trampling down of the servile classes to sustain the power and glory of the governing class? I know of none

BUT THE INDIAN DUDS DO NOT GET IT !

THHE ENTIRE POST PRODUCTION SUPPLY CHAIN IS CONTROLLED BY BANIAS WHO ARE O/S THE FISCAL NET.IF FARMER GETS RS 1 THE USER PAYS RS 10 !

THAT RS 9 OF VALUE HAS A ECONOMIC VALUE ADDITION OF RS 2 ! IT CAN BE OUTSOURCED TO WALMARRT FOR RS 1.5

IF YOU ELIMNINATE THE BANIA - YOU HAVE PARADISE !

CHAIWALA IS A BANIA !

MORE THAN A 1000 YEARS AGO THE WHITE HUNS DESTROYED THE GUPTA EMPIRE TO BITS ! THE INDIAN DALITS ARE WAITING FOR A TURKISH/MONGOL AND PAKISANI/TALIBAN ATTACK !

THAT IS THE ONLY HOPE FOR INDDIAN DESTITUTES ! dindooohindoo

Ahmed, one needs to keep in mind India's HUGE working age population which is very likely greater than China's now. India has had reasonably good economic growth for an economy of its size, but not sufficient enough to generate jobs for them all. Despite having started economic liberalization since 1991, India has never had (and most likely never will have) the kind of breakneck infrastructural and industrial development and double digit GDP growth like China had since the 1990s, mostly due to difference in political systems. Starting any new industrial or infrastructural project in India has to contend with land acquisition woes, court cases, protests from opposition parties, public and other interest groups, change in govt policies and priorities after an election etc. - none of which matters in an authoritarian political system like China's where the govt owns all land, controls courts and does not tolerate dissent, agitation or political opposition. Pursuing liberal economic reforms itself have been like walking a tight rope in India due to protests from industrial workers and farmers (Modi govt's reversal of new farm laws in the face of sustained agitation by farmers of Haryana and Indian Punjab despite having passed the bills in Parliament being a recent example).

Hello Mr.Vineeth

You said that India can’t produce jobs for all with the economy of this size and with such and such economic growth .

My comment :

I am not expecting any country to produce jobs for all of its citizen , even in western countries and America this is not possible . And you can’t expect all the people living in a country to be working . Some people in a country prefer to have their own businesses .

What I am saying is that why based on the level of economic growth which India actually enjoyed over few decades , still their is huge shortage of jobs in India ? Their should be enough jobs in India to accommodate atleast 70% of the jobless students and people in the country .

Mr. Vineeth

Yes the actual progress of economy in China started after 1990s and as far as I remember and know even the actual progress of economy of India started after 1990s when economic reforms were introduced in the country . The economy of India started to move fast and grow after 1990s and we can say that both India and China were on the same page when it comes to the exact year of starting economic progress but why is it that their is less joblessness in China and much less poverty in China as compared to India ?

As India's rank falls to 111, here's everything about Global Hunger Index

https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/as-india-s-rank-falls-to-111-here-s-everything-about-global-hunger-index-123101300136_1.html

India's ranking in the Global Hunger Index 2023 fell to 111 out of 125 countries from 107 in 2022. The index, released on Thursday, also stated that India has the highest child-wasting rate in the world at 18.7 per cent, reflecting acute undernutrition.

With a score of 28.7, India has a level of hunger that is "serious". India's neighbouring countries Pakistan (102nd), Bangladesh (81st), Nepal (69th) and Sri Lanka (60th) fared better than it in the index.

South Asia and Africa South of the Sahara are the world regions with the highest hunger levels, with a GHI score of 27 each, indicating serious hunger.

"India has the highest child wasting rate in the world, at 18.7 per cent, reflecting acute undernutrition," the report based on the index stated. Wasting is measured based on children's weight relative to their height.

According to the index, the rate of undernourishment in India stood at 16.6 per cent and under-five mortality at 3.1 per cent. The report also said that the prevalence of anaemia in women aged between 15 and 24 years stood at 58.1 per cent.

The government, however, rejected the index, calling it a flawed measure of "hunger" that does not reflect India's actual position.

The Women and Child Development Ministry said the index suffers from "serious methodological issues and shows a malafide intent".

What is the Global Hunger Index?

Global Hunger Index is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger at global, regional, and national levels. It is released by the Alliance2015, a network of seven European non-government organisations engaged in humanitarian and development action.

The index captures three dimensions of hunger: insufficient availability of food, shortfalls in the nutritional status of children and child mortality (which is, to a large extent, attributable to undernutrition).

It, accordingly, includes three equally weighted indicators: the proportion of people who are food energy-deficient, as estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the prevalence of underweight in children aged under five years, as compiled by the World Health Organisation (WHO), and the mortality rate of children aged under five years, as reported by UNICEF.

A regression analysis of the global hunger index on GNI per capita is performed to identify countries that are notably better or worse off with regard to hunger and undernutrition than would be expected from their GNI per capita. Countries are ranked on a 100-point scale, with 0 and 100 being the best and worst possible scores, respectively.

What does GHI 2023 say about the world?

The 2023 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows that, after many years of advancement up to 2015, progress against hunger worldwide remains largely at a standstill. The 2023 GHI score for the world is 18.3, considered moderate and less than one point below the world's 2015 GHI score of 19.1.

Furthermore, since 2017, the prevalence of undernourishment, one of the indicators used in the calculation of GHI scores, has been on the rise, and the number of undernourished people has climbed from 572 million to about 735 million.

To Understand India’s Economy, Look Beyond the Spectacular Growth Numbers - The Wall Street Journal.

https://www.wsj.com/world/india/to-understand-indias-economy-look-beyond-the-spectacular-growth-numbers-31f5dd11

But the way India calculates its gross domestic product can at times overstate the strength of growth, in part by underestimating the weakness in its massive informal economy. There are also other indicators, such as private consumption and investment, that are pointing to soft spots. Despite cuts to corporate taxes, companies don’t appear to be spending on expansions.

-------------

BENGALURU, India—India is set to be the world’s fastest-growing major economy this year, but economists say the country’s headline growth numbers don’t tell the whole story.

The South Asian nation’s gross domestic product grew at more than 8% in its fiscal year ended in March compared with the previous year, driven by public spending on infrastructure, services growth, and an uptick in manufacturing. That would put India well ahead of China, which is growing at about 5%, and on track to hit Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s goal of becoming a developed nation by 2047.

But the way India calculates its gross domestic product can at times overstate the strength of growth, in part by underestimating the weakness in its massive informal economy. There are also other indicators, such as private consumption and investment, that are pointing to soft spots. Despite cuts to corporate taxes, companies don’t appear to be spending on expansions.

“If people were optimistic about the economy, they would invest more and consume more, neither of which is really happening,” said Arvind Subramanian, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and former chief economic adviser to the Modi government.

Private consumption, the biggest contributor to GDP, grew at 4% for the year, still slower than pre-pandemic levels. What’s more, economists say, it could have been even weaker if the government hadn’t continued its extensive food-subsidy program that began during the pandemic.

The problem is driven in part by how India emerged from the pandemic. Big businesses and people who are employed in India’s formal economy are generally doing well, but most Indians are in the informal sector or agriculture, and many of them lost work.

While India’s official data last year put unemployment at around 3%, economists also closely track data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a private economic research firm. It put unemployment at 8% for the year ended March.

At a small tea-and-cigarette stall in the southern city of Bengaluru, 55-year-old Ratnamma said many of her customers in the neighborhood, which once bustled with tech professionals and blue-collar workers, have moved out of the city and returned to rural villages. Some have come back, but she has fewer customers than she once did.

“Where did everyone go?” she said.

She makes about $12 a day in sales, she said, compared with as much as $100 on a good day in the past. It isn’t enough to cover her living expenses or repay a business loan she took out six months ago.

Economists say that the informal sector has been through three shocks in a decade—a 2016 policy aimed at tax evasion called “demonetization” that wiped out 90% of the value of India’s paper currency, a tax overhaul the following year that created more paperwork and expenses for small businesses, and the pandemic.

Pakistan inflation slows to 11.8% in May, lowest in 30 months

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/pakistan-inflation-slows-to-11-8-in-may-lowest-in-30-months/ar-BB1nw9LN?item=flightsprg-tipsubsc-v1a?season=2024

ISLAMABAD (Reuters) - Pakistan's consumer price index (CPI) in May rose 11.8% from a year earlier, data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics showed on Monday, the lowest reading in 30 months and below the finance ministry's projections.

The lowest reading comes a week before the central bank meets to review the key rate which has remained at a historic high of 22% for seven straight policy meetings.

Pakistan has been beset by inflation above 20% since May 2022. Last year in May, inflation jumped as high as 38% as the country navigated reforms as part of an International Monetary Fund bailout programme. However, inflation has since slowed down.

Month-on-month consumer prices fell 3.2%, the biggest such drop in more than two years.

In its monthly economic report released last week, Pakistan's finance ministry said it expected inflation to hover between 13.5% and 14.5% in May and ease to 12.5% to 13.5% by June 2024.

"The inflation outlook for May 2024 continues on a downward trajectory, attributed to elevated inflation levels (in the) previous year and improvements in (the) domestic supply chain of perishable items, staple food like wheat and (a) reduction in transportation costs," the report said.

The actual readings have come in even lower due to a sharper dip in food prices, said Amreen Soorani, head of research at JS Global Capital.

Pakistani YouTubers And Praise India Movement in Pakistan - India Today

"Indians love people from abroad lauding their achievements, but seem to derive the biggest satisfaction when Pakistanis gush over India's success. Pakistanis have understood that and have tapped into that, creating an entire industry of YouTubers in Pakistan"

https://www.indiatoday.in/sunday-special/story/praise-india-movement-pakistan-reaction-videos-on-indian-cricket-food-politics-youtube-shorts-pakistani-youtubers-2553682-2024-06-16

-------

There is a Praise India Movement in Pakistan if one goes by the pro-India videos being churned out by Pakistani YouTubers. If some are praising India's space programme, others are talking about its economic and political successes. Why are Pakistanis creating such YouTube videos, and that too, in such huge numbers?

"India did a big favour to Pakistan. It was also a tight slap for those Pakistanis who said India would deliberately lose to the USA to get Pakistan out of the T20 World Cup tournament. India is the world's number one team, and can never lose to the US," a man in a black salwar kameez states emphatically, looking at the camera. The person isn't an Indian gushing at India's victory over the USA in a T20 World Cup match, but a Pakistani speaking to a popular Pakistani YouTuber at a market in Pakistan.

The video by YouTuber Shaila Khan on her channel Naila Pakistani Reaction has over 3 lakh views in a day.

Indians love people from abroad lauding their achievements, but seem to derive the biggest satisfaction when Pakistanis gush over India's success. Pakistanis have understood that and have tapped into that, creating an entire industry of YouTubers in Pakistan.

There are 5,500 channels and over 84,000 videos just with the hashtag pakistanireactiononindia on YouTube. The number of channels, tracked by IndiaToday.In since November 2023, has grown by 1,000 in a matter of six months. Over 5,000 videos have been added under this hashtag since November.

We are talking about just one hashtag. There are several others with India-related content, some of which every Indian would have come across while scrolling through shorts and videos on YouTube.

This content boom by Pakistani YouTubers has sparked a Praise India Movement in Pakistan.

Seeing is believing, especially if it is about YouTube.

So, just try keying in #Pakistani on the YouTube search bar. The first few results are Pakistani Reaction, Pakistani Reaction on India and Pakistani Public Reaction -- all to do with content related to India.

Such is the rage that even #PakistaniDrama, one of Pakistan's biggest cultural exports, trends below the #PakistaniReaction.

WHAT ARE THE PRO-INDIA VIDEOS PAKISTANIS ARE CREATING

There was a flood of videos by Pakistani YouTubers lauding Team India right after their victory over the USA.

Though cricket is one of the favourites, the range of 'praise India' videos spans from India's economic might to infrastructural developments; from gastronomic delights to space programmes. Then there are videos of Pakistanis describing in amazement their wonderful discoveries during their first visit to India.

You name it, and they have it. There are Pakistani reaction clips to every Top 10 video, featuring India's shopping malls, highways, airports, college campuses, cars, bikes and even golgappas.

Post a Comment