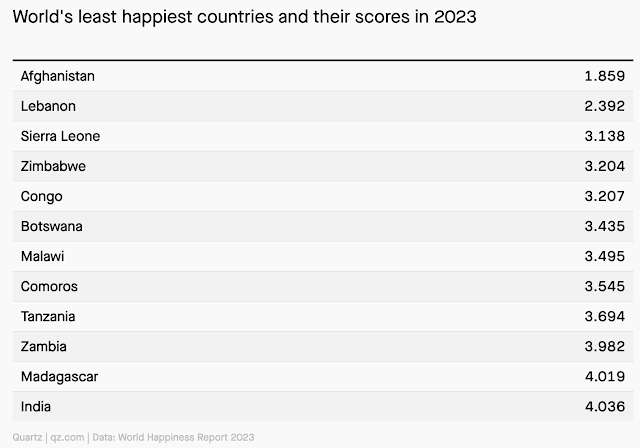

India occupies 126th position among 137 nations ranked in the World Happiness Report 2023 released by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. In South Asia, Pakistan (score 4.555) ranks 108, Sri Lanka 112, Bangladesh (4.282) 118 and India 126 (4.036). Only Taliban-ruled Afghanistan ranks worse at 137. Finland is the happiest nation in the world, followed by Denmark and Iceland in 2nd and 3rd place.

|

| Least Happy Countries in 2023. Source: Quartz |

|

| Bottom Third Countries in World Happiness Rankings. Source: World Happiness Report |

The latest country rankings show life evaluations (answers to the Cantril ladder question) for each country, averaged over a 3 year period from 2020-2022. The Cantril ladder asks respondents to think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10 and the worst possible life being a 0. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale. The rankings are from nationally representative samples for the years 2020-2022.

|

| World Happiness Map 2023. Source: Visual Capitalist |

Happiness Scores Trend:

After climbing to a high of 5.65 in 2019, Pakistan's happiness scores have declined in recent years, reaching a low of 4.52 during the Covid pandemic. The most recent value is 4.555 for 2023.

|

| Recent Happiness Scores in Pakistan. Source: The Global Economy |

India's happiness scores have been declining every year since 2013, reaching a low of 3.78 during the Covid pandemic. The most recent value is 4.036 for 2023.

|

| Recent Happiness Scores in India. Source: The Global Economy |

Causes of Unhappiness:

Lack of social connections during covid lockdown, along with severe unemployment, high inflation and healthcare worries, took a toll on mental health of Indians, according to the experts quoted by the Indian media.

|

| Suicide Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank |

Rising Suicides:

Indian experts' observations are supported by the Indian government data showing a marked increase in suicide rate in India. India saw the highest suicide rate (of 12 suicides per 100,000 population) since the beginning of this century, according to The Hindu. Experts say a lot of suicides would have gone unreported and that the numbers and suicide rates could have gone up in 2022 as well.

|

| Suicide Rate in India. Source: The Hindu |

High Unemployment:

India's unemployment rate rose to 7.45% in February 2023 from 7.14% in the previous month, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). CMIE’s weekly labor market analysis showed a marginal improvement in India’s labor participation rate to 39.92% in February compared to 39.8% in January 2023 resulting in an increase in the labour force from 440.8 million to 442.9 million.

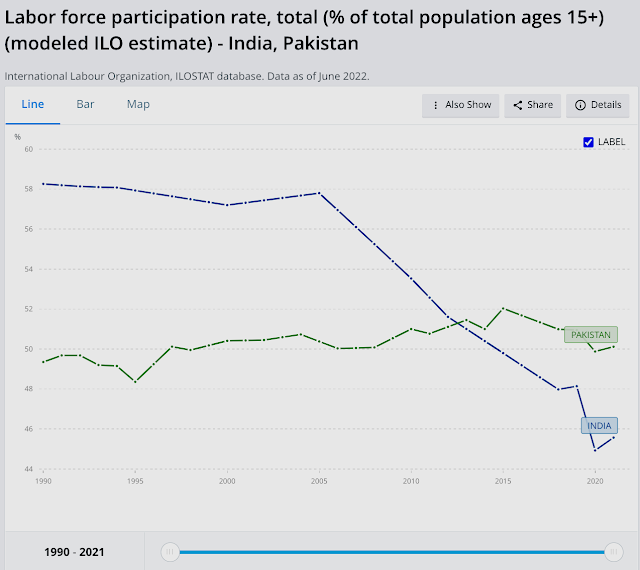

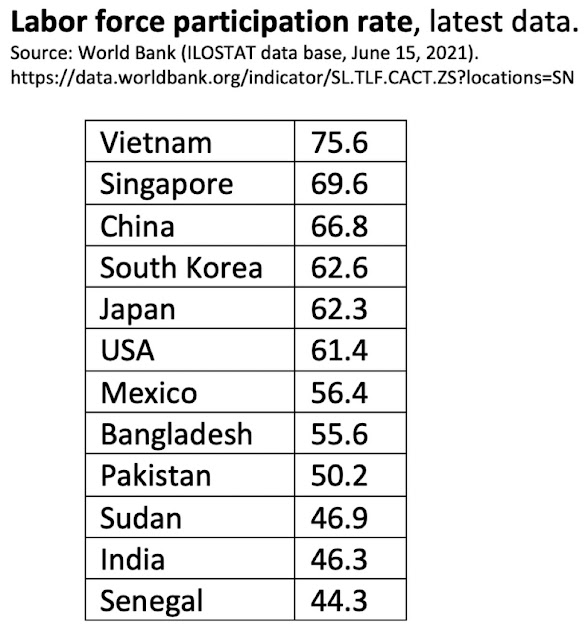

"India’s LPR is much lower than global levels. According to the World Bank, the modeled ILO estimate for the world in 2020 was 58.6 per cent. The same model places India’s LPR at 46 percent. India is a large country and its low LPR drags down the world LPR as well. Implicitly, most other countries have a much higher LPR than the world average. According to the World Bank’s modeled ILO estimates, there are only 17 countries worse than India on LPR. Most of these are middle-eastern countries. These are countries such as Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Syria, Senegal and Lebanon. Some of these countries are oil-rich and others are unfortunately mired in civil strife. India neither has the privileges of oil-rich countries nor the civil disturbances that could keep the LPR low. Yet, it suffers an LPR that is as low as seen in these countries".

|

| Labor Participation Rates in India and Pakistan. Source: World Bank/ILO |

|

| Labor Participation Rates for Selected Nations. Source: World Bank/ILO |

Youth unemployment for ages15-24 in India is 24.9%, the highest in South Asia region. It is 14.8% in Bangladesh 14.8% and 9.2% in Pakistan, according to the International Labor Organization and the World Bank.

|

| Youth Unemployment in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Source: ILO, WB |

In spite of the headline GDP growth figures highlighted by the Indian and world media, the fact is that it has been jobless growth. The labor participation rate (LPR) in India has been falling for more than a decade. The LPR in India has been below Pakistan's for several years, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

| Indian GDP Sectoral Contribution Trend. Source: Ashoka Mody |

|

| Indian Employment Trends By Sector. Source: CMIE Via Business Standard |

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

India has performed particularly poorly because of one of the world's strictest lockdowns imposed by Prime Minister Modi to contain the spread of the virus.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

45 comments:

Dear Sir and members of this blog

Thanks for this post about position of India in world happiness report of 2023 . Now I think Mr. Uzair Younus so called “ Analyst from Pakistan “ who said in his interview that BJP government has transformed lives of many people of India .

If this is really true then why is India

so badly lagging behind and ranked so low in this report of world happiness in 2023?

#Tech #Startup Layoffs in #India. Over 36,400 people lost their jobs in India in the last couple of years. 5 companies have laid off 75% of their workforce. #Indian startups which laid off workers include #Byju, #UpAcademy, #Ola. #economy #unemployment

https://www.livemint.com/news/india/thousands-have-lost-jobs-in-india-these-layoff-numbers-will-blow-your-mind-11679462788841.html

Over 36,400 people lost their jobs in India in the last couple of years, as per the latest data from layoff.fyi. Nine companies, including Lido Learning, SuperLearn and GoNuts, have laid off 100% of its workforce. According to the website that tracks tech sector job cuts, five companies laid off 70-75% of its workforce. Such companies include GoMechanic, PhableCare and MFine.

Byju’s is leading the number of layoffs with 4,000 employees losing their jobs at the company. WhiteHat Jr laid off 1,800 employees in January 2021 and then 300 in June 2022. Bytedance terminated 1,800 employees in January 2021. In June 2020, Paisabazaar let go 1,500 people, 50% of its workforce.

Ola has laid off its employees four times since May 2020. In May 2020, it laid off 1,400 employees while it sacked 1,000 people in July 2022. In September 2022, it asked 200 people to leave and terminated 200 employees again in January 2023.

Unacademy has laid off 1,500 employees so far, all of it came in 2022. The layoff came in three phases; 1,000 in April, 150 in June and 350 in November.

On the global front, 503 tech companies have laid off 148,165 employees so far this year. The year 2022 was challenging for the technology industry and startups. At least 1.6 lakh workers lost their jobs in 2022, and the year 2023 has begun on a similar note.

Amazon has contributed to the worsening outlook for the technology industry by terminating an additional 9,000 employees. This comes after they had previously fired 18,000 employees. Meanwhile, a significant number of other companies have also laid off a substantial amount of workers this year, with almost 1.5 lakh individuals being affected to date.

Dear Sir

Ramazan Mubarak to you and to all Muslims and Pakistanis.

Thanks for sharing this article but what could probably be the reason for such layoffs at jobs in India ?

Thanks

Why So Sad? #India’s Rank On #WorldHappinessIndex2023 Saddens Industrialist Harsh Goenka. “I am saddened to see India perform miserably in what I believe is the most important parameter to reflect the state of the nation ‘Global Happiness Index 2023’" https://www.news18.com/buzz/why-so-sad-indias-rank-on-world-happiness-index-upsets-harsh-goenka-7353913.html

he World Happiness Report is out and the result has saddened a lot of Indians. Among them is industrialist Harsh Goenka, who is not satisfied with the country’s “miserable” position on the index. India is ranked 126th among 146 nations, with a score of 4.00 on a scale of 0 to 10. The annual United Nations-sponsored index is based on people’s own assessment of their happiness, economic and social data. India’s position is a sharp jump from the 136th spot that India occupied last year, yet Harsh Goenka feels that much more needs to be done. The RPG Enterprises chairman, in a recent tweet, asked what could be done to better the situation.

“I am saddened to see India perform miserably in what I believe is the most important parameter to reflect the state of the nation ‘Global Happiness Index 2023’. What is the reason and what should we do about it?” Harsh Goenka wrote while sharing some data of the Global Happiness Index 2023.

Many users were just as concerned as Harsh Goenka and put forward many reasons as a possibility for India’s low rank in the report. “We need to improve our work-family-fitness balance,” one person suggested.

Some stated that there was too much divisiveness and hate in India these days.

A few users cited price rises as the reason for unhappiness. “Low per capita income and rising cost could be a reason,” a comment read.

Others advised newer ways to achieve work-life balance. “More than monetary, I believe that recreation is a big part of this problem… For an Indian the only sort of relief from the problems of life are cinema and cricket. We need to think of new ways to balance out work and life,” an individual noted.

But quite a few people questioned the data collection of the Global Happiness Index, calling it “biased.”

“Have you looked into how it is calculated and the integrity of the data?” another person asked.

India’s neighbours have fared better when it comes to the World Happiness Report. Pakistan is at 108th place, while Bangladesh occupies 118th spot. Nepal is 78th and Sri Lanka is ranked 112th on the index.

As per the World Happiness Report 2023, Finland is the happiest country in the world. Denmark and Iceland occupied the second and third positions. Afghanistan is at the bottom of the table once again. Since 2020, the country has remained at the lowest spot on the index. The World Happiness Report has been published yearly since 2012.

#India’s #Modi has a problem: high #economic #growth but few #jobs. Persistently high #unemployment poses #election challenge as youth stuck in menial #labor that does not match skills. No wonder India ranks among world's saddest nations. #Happiness https://www.ft.com/content/6886014f-e4cd-493c-986b-1da2cfc8cdf2

Kiran VB, 29, a resident of India’s tech capital Bangalore, had hoped to work in a factory after finishing high school. But he struggled to find a job and started working as a driver, eventually saving up over a decade to buy his own cab.

“The market is very tough; everybody is sitting at home,” he said, describing relatives with engineering or business degrees who also failed to find good jobs. “Even people who graduate from colleges aren’t getting jobs and are selling stuff or doing deliveries.”

His story points to an entrenched problem for India and a growing challenge for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government as it seeks re-election in just over a year’s time: the country’s high-growth economy is failing to create enough jobs, especially for younger Indians, leaving many without work or toiling in labour that does not match their skills.

The IMF forecasts India’s economy will expand 6.1 per cent this year — one of the fastest rates of any major economy — and 6.8 per cent in 2024.

However, jobless numbers continue to rise. Unemployment in February was 7.45 per cent, up from 7.14 per cent the previous month, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

“The growth that we are getting is being driven mainly by corporate growth, and corporate India does not employ that many people per unit of output,” said Pronab Sen, an economist and former chief adviser to India’s Planning Commission.

“On the one hand, you see young people not getting jobs; on the other, you have companies complaining they can’t get skilled people.”

Government jobs, coveted as a ticket to life-long employment, are few in number relative to India’s population of nearly 1.4bn, Sen said. Skills availability is another issue: many companies prefer to hire older applicants who have developed skills that are in demand.

“A lot of the growth in India is driven by finance, insurance, real estate, business process outsourcing, telecoms and IT,” said Amit Basole, professor of economics at Azim Premji University in Bangalore. “These are the high-growth sectors, but they are not job creators.”

Figuring out how to achieve greater job growth, particularly for young people, will be essential if India is to capitalise on a demographic and geopolitical dividend. The country has a young population that is set to surpass China’s this year as the world’s largest. More companies are looking to redirect supply chains and sales away from reliance on Chinese suppliers and consumers.

India’s government and states such as Karnataka, of which Bangalore is the capital, are pledging billions of dollars of incentives to attract investors in manufacturing industries such as electronics and advanced battery production as part of the Modi government’s “Make in India” drive.

The state also recently loosened labour laws to emulate working practices in China following lobbying by companies including Apple and its manufacturing partner Foxconn, which plans to produce iPhones in Karnataka.

However, manufacturing output is growing more slowly than other sectors, making it unlikely to soon emerge as a leading generator of jobs. The sector employs only about 35mn, while IT accounts for a scant 2mn out of India’s formal workforce of about 410mn, according to the CMIE’s latest household survey from January to February 2023.

According to a senior official in Karnataka, highly skilled applicants with university degrees are applying to work as police constables.

#India’s #Modi has a problem: high #economic #growth but few #jobs. Persistently high #unemployment poses #election challenge as youth stuck in menial #labor that does not match skills. No wonder India ranks among world's saddest nations. #Happiness https://www.ft.com/content/6886014f-e4cd-493c-986b-1da2cfc8cdf2

The Modi government has shown signs of being attuned to the issue. In October, the prime minister presided over a rozgar mela, or an employment drive, where he handed over appointment letters for 75,000 young people, meant to showcase his government’s commitment to creating jobs and “skilling India’s youth for a brighter future”.

But some opposition figures derided the gesture, with the Congress party president Mallikarjun Kharge saying the appointments were “just too little”. Another politician called the fair “a cruel joke on unemployed youths”.

Rahul Gandhi, the scion of the family behind the Congress party, has signalled that he intends to make unemployment a point of attack for the upcoming election, in which Modi is on track to win a third term.

“The real problem is the unemployment problem, and that’s generating a lot of anger and a lot of fear,” Gandhi said in a question-and-answer session at Chatham House in London last month.

“I don’t believe that a country like India can employ all its people with services,” he added.

Ashoka Mody, an economist at Princeton University, invoked the word “timepass”, an Indian slang term meaning to pass time unproductively, to explain another phenomenon plaguing the jobs market: underemployment of people in work not befitting their skills.

“There are hundreds of millions of young Indians who are doing timepass,” said Mody, author of India is Broken, a new book critiquing the economic policies of successive Indian governments since independence. “Many of them are doing so after multiple degrees and colleges.”

Dildar Sekh, 21, migrated to Bangalore after completing a high school course in computer programming in Kolkata.

After losing out in the intense competition for a government job, he ended up working at Bangalore’s airport with a ground handling company that assists passengers in wheelchairs, for which he is paid about Rs13,000 ($159) per month.

“The work is good, but the salary is not good,” said Sekh, who dreams of saving enough money to buy an iPhone and treat his parents to a helicopter ride.

“There is no good place for young people,” he added. “The people who have money and connections are able to survive; the rest of us have to keep working and then die.”

India is one of the rare countries in the world where GDP growth is inversely proportional to happiness.

It means either one of two things.

1) India’s growth numbers are fictitious

2) India’s growth has disproportionately benefited only a tiny upper-class / upper-caste elite

Dear Sir

Pls check this , this is a video of Junaid Akram from Karachi on YouTube . He is a famous YouTuber in Pakistan and just few hours ago he has made a video on YouTube in which he has talked about the progress which India has made in technology and science specially in space programs . He gave examples of ISRO( Indian Space Research Organizations) and have talked about its success since last few years .

Can you pls make a blog about it and explain how many countries including Isreal , France and other countries have helped Indian space agency ( ISRO) in what ever progress it has made in space programs and space technology ?

Thanks

Dear Sir

Sorry I forgot to post the video link of Junaid Akram . This is his video link :

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Bb_jKyyQcFQ

Sir I would appreciate if you could make a blog about it and also explain the realities of how ISRO made progress .

Thanks

Any thought on South Korea being 'sadder' than El Salvador and Honduras where people get killed in broad daylight?

Japan 'sadder' than Nicaragua and Guatemala where country is ruled by Narco-traffickers and human life is worth nothing?

EP: "Any thought on South Korea being 'sadder' than El Salvador and Honduras where people get killed in broad daylight?"

Watch Squid Game. It is a powerful indictment of capitalism as practiced in many countries, including South Korea. It has brought to light high levels of inequality and household debt in South Korea. The total household debt of $1.5 trillion is about the size of its entire GDP, among the highest in the world. By comparison, formal household debt in Pakistan is just 4% of its GDP, according to the IMF. It can be explained by the fact that the availability of mortgage financing, car loans and credit cards is very limited in Pakistan.

https://www.southasiainvestor.com/2021/10/squid-games-dystopian-korean-drama.html

Modi's monsters (cyber cell) in twitter:

India is a happy country, but lags in rankings because Indian muslims (traitors) downvote in every survey

Zen: "Modi's monsters (cyber cell) in twitter:India is a happy country, but lags in rankings because Indian muslims (traitors) downvote in every survey"

Most Indians reject all international rankings in which India performs poorly.

Indian government dismissed India's low ranking in World Hunger Index even though it was based entirely on India's official data.

Please read below:

https://www.logically.ai/articles/indias-hunger-problem-ghi

Regardless of the GHI rankings, the Indian government’s own data shows that India has a serious hunger problem, at least when it comes to children.

According to the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-V) for 2019-21, the percentage of children wasted under five years was 19.3 percent. Child stunting in the same age bracket was at 35.5 percent. These figures are used for India’s assessment in the GHI, with it faring the highest in child wasting.

While there was slight improvement by under three percentage points on both these indicators compared to 2015 to 2016, the data included concerning findings on ‘severe’ malnutrition among children. Analysis of district-level NFHS data reveals that almost half of Indian districts recorded an increase in severe wasting or severe acute malnutrition between 2015-2016 and 2019-2021. Additionally, data shows anaemia levels among children increased by almost ten percent in the same time period.

“We do not need the GHI to know that India has a serious problem of undernutrition. The levels of stunting are high and are not declining fast enough. One reason for the slow progress on this is our unwillingness to acknowledge the seriousness of this issue," Khera said.

The government’s response to the GHI can be seen as an indication of dismissing the issue. The central government argues that it is undertaking extensive programmes to ensure food security such as distribution of additional foodgrains to 80 crore beneficiaries from March 2020. But activists and experts allege that this doesn’t solve the problem of poor nutrition.

Nearly 71 percent Indians cannot afford a healthy diet, even with public programmes factored in, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down To Earth reported in June this year.

“Close to a 100 million people stand excluded out of India's public distribution system since the government is still using the 2001 population data from the Census rather than updated estimates for 2022,” said Biraj Patnaik, former Principal Adviser to the Commissioners of the Supreme Court in the Right to Food case. “Rather than quibbling over global rankings, as a country we must address the underlying causes of malnutrition which go beyond food and cover other social determinants” Patnaik said.

“Of course India has the largest food security programme, but the evidence is suggesting it's not enough. Moreover, after more than 75 years of Independence, our aspiration cannot just be improving cereal consumption; we need to work on providing decent quality of food to our people," Prasad said.

I thought you understand sarcasm. However, on a different note, I see some of these surveys Eurocentric.

In pretty much every survey, Finland or Iceland is no.1, Denmark is 2, Sweden and Norway are 3rd and 4th ;-)

It is true that these countries have excellent social safety net, but other factors like quality of family life, having some food that tastes like food etc. are not taken account. Pakistanis with suicide bombing etc. have probably no time to be unhappy either.

Zen: "Pakistanis with suicide bombing etc. have probably no time to be unhappy either"

The fact that Pakistanis (108) rank higher than Indians (126) doesn't mean they are not unhappy.

Both India and Pakistan rank in the bottom third of 137 countries surveyed in the latest happiness rankings.

Dear Sir

Thanks for posting this article .

According to this article out of the total workforce of India which is 410 million , hardly only 2 million people work in IT industry of India .

Sir if this is really true ? If such small percentage of people work in the IT sector of India , then how is it possible that the software exports of India are much higher than neighbouring countries ?

Thanks

Ahmed: "Sir if this is really true ? If such small percentage of people work in the IT sector of India , then how is it possible that the software exports of India are much higher than neighbouring countries?"

India has no "software exports". India's forex tech earnings come from tech services provided to foreign firms by H1B type work visa workers on the payrolls of Indian body shops like Infosys, TCS, Wipro etc.

Glassdoor, a company that reviews employers, calls all of them body shops.

https://www.glassdoor.com/Reviews/Employee-Review-Infosys-RVW36839425.htm

https://www.glassdoor.com/Reviews/Employee-Review-Wipro-RVW23275846.htm

https://www.glassdoor.com/Reviews/Employee-Review-Tata-Consultancy-Services-RVW2307652.htm

#SouthKorean government was this week forced to rethink a plan that would have raised its cap on #workinghours to 69 per week, up from the current limit of 52, after sparking a backlash among Millennials and Generation Z workers. #SouthKorea https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/18/asia/south-korea-longer-work-week-debate-intl-hnk

Shorter workweeks to boost employee mental health and productivity may be catching on in some places around the world, but at least one country appears to have missed the memo.

The South Korean government was this week forced to rethink a plan that would have raised its cap on working hours to 69 per week, up from the current limit of 52, after sparking a backlash among Millennials and Generation Z workers.

Workers in the east Asian powerhouse economy already face some of the longest hours in the world – ranking fourth behind only Mexico, Costa Rica and Chile in 2021, according to the OECD – and death by overwork (“gwarosa”) is thought to kill scores of people every year.

Yet the government had backed the plan to increase the cap following pressure from business groups seeking a boost in productivity – until, that is, it ran into vociferous opposition from the younger generation and labor unions.

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s senior secretary said Wednesday the government would take a new “direction” after listening to public opinion and said it was committed to protecting the rights and interests of Millennial, Generation Z and non-union workers.

Raising the cap had been seen as a way of addressing the looming labor shortage the country faces due to its dwindling fertility rate, which is the world’s lowest, and its aging population.

But the move was widely panned by critics who argued tightening the screw on workers would only make matters worse; experts frequently cite the country’s demanding work culture and rising disillusionment among younger generations as driving factors in its demographic problems.

It was only as recently as 2018 that, due to popular demand, the country had lowered the limit from 68 hours a week to the current 52 – a move that at the time received overwhelming support in the National Assembly.

The current law limits the work week to 40 hours plus up to 12 hours of compensated overtime – though in reality, critics say, many workers find themselves under pressure to work longer.

“The proposal does not make any sense… and is so far from what workers actually want,” said Jung Junsik, 25, a university student from the capital Seoul who added that even with the government’s U-turn, many workers would still be pressured to work beyond the legal maximum.

>The fact that Pakistanis (108) rank higher than Indians (126) doesn't mean they are >not unhappy.

right, but any claim otherwise would have been total non-sense. I agree that there is a tendency in India (it is fashionable in fact) to dismiss international surveys. But, this happiness survey just like best food country survey (which Denmark wins) gives me a good laugh. I'm sure that Danish people are happy when they eat their unspiced, flavourless food. But is it any objective then to claim that they have best food? Same about happiness. Maybe, Indians are more likely to complaint about their life circumstances to strangers and criteria itself are eurocentric. HDI on the other hand is a legit thing.

The fact that Pakistan is marginally above India on this survey made you jump on this, however.

India slipping on way to meeting UN-mandated SDGs: CSE-DTE

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/india-slipping-on-way-to-meeting-un-mandated-sdgs-cse-dte-88485

https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/pakistan

https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/india

Country (India) facing challenges in 11 of the 17 SDGs; states’ individual performances ranked as well (Pakistan facing challenges in 12 of 17 SDGs)

India has been stumbling over meeting the United Nations-mandated sustainable development goals (SDG). Over the past five years, it has slipped nine spots — ranking 121 in 2022, according to an annual report by Down To Earth, the fortnightly magazine by New Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment.

India is behind its neighbours Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh and Pakistan was lagging close behind at 125. The deadline for the goals is 2030, which is looming ahead — but India is facing challenges in 11 of the 17 SDGs, according to State of India’s Environment 2023 (SoE), released on March 23, 2023.

The 2023 report covered an extensive gamut of subject assessments, ranging from climate change, agriculture and industry to water, plastics, forests and biodiversity.

The report looked at states’ performances as well. “An alarmingly high number of states have slipped in their performance of SDGs 4, 8, 9, 10 and 15,” said Richard Mahapatra, managing editor of DTE and one of the editors of the SoE.

These numbers refer to the goals on quality education; decent work and economic growth; industry, innovation and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; and life on land, respectively.

In SDG 4 (quality education), for instance, 17 states saw a dip in their performance between 2019 and 2020. SDG 15 — life on land — has 25 states performing below average.

The goal on clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) has become more distant for 15 states, while 22 states are slipping in SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth).

Concurrently, there has been improvement by states as well in several goals — SDGs 1 (no poverty), 2 (zero hunger), 3 (good health and well-being), 5 (gender equality), 7 (affordable and clean energy), 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and 12 (responsible consumption and production).

“All the data that we are using here is from credible, and in many cases, from the government’s own sources,” said Mahapatra.

DTE’s research team says that India’s ranking has been taken from the SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2022 by Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network for the time period 2017-2022.

The state-level ranking is based on the government think tank NITI Aayog’s SDG India Index Report 2020-21. Here, the DTE team has analysed the 2020 and 2019 scores.

Hype over #India’s #economic boom is dangerous myth masking real problems. It’s built on a disingenuous numbers game.

No silver bullet that will fix weak job creation, a small, uncompetitive #manufacturing sector & gov’t schemes fattening corporate profits

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indias-economic-boom-dangerous-myth-masking-real-problems

by Ashoka Mody

Indian elites are giddy about their country’s economic prospects, and that optimism is mirrored abroad. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that India’s GDP will increase by 6.1 per cent this year and 6.8 per cent next year, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Other international commentators have offered even more effusive forecasts, declaring the arrival of an Indian decade or even an Indian century.

In fact, India is barrelling down a perilous path. All the cheerleading is based on a disingenuous numbers game. More so than other economies, India’s yo-yoed in the three calendar years from 2020 to 2022, falling sharply twice with the emergence of Covid-19 and then bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels. Its annualised growth rate over these three years was 3.5 per cent, about the same as in the year preceding the pandemic.

Forecasts of higher future growth rates are extrapolating from the latest pandemic rebound. Yet, even with pandemic-related constraints largely in the past, the economy slowed in the second half of 2022, and that weakness has persisted this year. Describing India as a booming economy is wishful thinking clothed in bad economics.

Worse, the hype is masking a problem that has grown in the 75 years since independence: anaemic job creation. In the next decade, India will need hundreds of millions more jobs to employ those who are of working age and seeking work. This challenge is virtually insurmountable considering that the economy failed to add any net new jobs in the past decade, when 7 million to 9 million new jobseekers entered the market each year.

This demographic pressure often boils over, fuelling protests and episodic violence. In 2019, 12.5 million people applied for 35,000 job openings in the Indian railways – one job for every 357 applicants. In January 2022, railway authorities announced they were not ready to make the job offers. The applicants went on a rampage, burning train cars and vandalising railway stations.

With urban jobs scarce, tens of millions of workers returned during the pandemic to eking out meagre livelihoods in agriculture, and many have remained there. India’s already-distressed agriculture sector now employs 45 per cent of the country’s workforce.

Farming families suffer from stubbornly high underemployment, with many members sharing limited work on plots rendered steadily smaller through generational subdivision. The epidemic of farmer suicides persists. To those anxiously seeking support from rural employment-guarantee programmes, the government unconscionably delays wage payments, triggering protests.

For far too many Indians, the economy is broken. The problem lies in the country’s small and uncompetitive manufacturing sector.

India is Broken

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3215379/hype-over-indias-economic-boom-dangerous-myth-masking-real-problems

by Ashoka Mody

Since the liberalising reforms of the mid-1980s, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has fallen slightly to about 14 per cent, compared to 27 per cent in China and 25 per cent in Vietnam. India commands less than a 2 per cent global share of manufactured exports, and as its economy slowed in the second half of 2022, the manufacturing sector contracted further.

Yet it is through exports of labour-intensive manufactured products that Taiwan, South Korea, China and now Vietnam came to employ vast numbers of their people. India, with its 1.4 billion people, exports about the same value of manufactured goods as Vietnam does with 100 million people.

Those who believe that India stands at the cusp of greatness usually focus on two recent developments. First, Apple contractors have made initial investments to assemble high-end iPhones in India, leading to speculation that a broader move away from China by manufacturers will benefit India despite the country’s considerable quality-control and logistical problems.

while such an outcome is possible, academic analysis and media reports are discouraging. Economist Gordon H. Hanson says Chinese manufacturers will move labour-intensive manufacturing from the country’s expensive coastal hubs to its less-developed interior, where production costs are lower.

Moreover, investors moving out of China have gone mainly to Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia, which like China are members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. India has eschewed membership in this trade bloc because its manufacturers fear they will be unable to compete once other member states gain easier access to the Indian market.

As for US producers pulling away from China, most are “near-shoring” their operations to Mexico and Central America. Altogether, while some investment from this churn could flow to India, the fact remains that inward foreign investment fell year on year in 2022.

The second source of hope is the Indian government’s Production-Linked Incentive Schemes, which were introduced in early 2021 to offer financial rewards for production and jobs in sectors deemed to be of strategic value. Unfortunately, as former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram G. Rajan and his co-authors warn, these schemes are likely to end up merely fattening corporate profits like previous sops to manufacturers.

India’s run with start-up unicorns is also fading. The sector’s recent boomrelied on cheap funding and a surge of online purchases by a small number of customers during the pandemic. But most start-ups have dim prospects for achieving profitability in the foreseeable future. Purchases by the small customer base have slowed and funds are drying up.

Looking past the illusion created by India’s rebound from the pandemic, the country’s economic prognosis appears bleak. Rather than indulge in wishful thinking and gimmicky industrial incentives, policymakers should aim to power economic development through investments in human capital and by bringing more women into the workforce.

India’s broken state has repeatedly avoided confronting long-term challenges and now, instead of overcoming fundamental development deficits, officials are seeking silver bullets. Stoking hype about an imminent Indian century will merely perpetuate the deficits, helping neither India nor the rest of the world.

Ashoka Mody, visiting professor of international economic policy at Princeton University, is the author of India is Broken: A People Betrayed, Independence to Today. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Adani’s business empire may or may not turn out to be the largest con in corporate history. But far greater dangers to civic morality, let alone democracy and global peace, are posed by those peddling the gigantic hoax of Modi’s India. Pankaj Mishra

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n08/pankaj-mishra/the-big-con

Modi has counted on sympathetic journalists and financial speculators in the West to cast a seductive veil over his version of political economy, environmental activism and history. ‘I’d bet on Modi to transform India, all of it, including the newly integrated Kashmir region,’ Roger Cohen of the New York Times wrote in 2019 after Modi annulled the special constitutional status of India’s only Muslim-majority state and imposed a months-long curfew. The CEO of McKinsey recently said that we may be living in ‘India’s century’. Praising Modi for ‘implementing policies that have modernised India and supported its growth’, the economist and investor Nouriel Roubini described the country as a ‘vibrant democracy’. But it is becoming harder to evade the bleak reality that, despoiled by a venal, inept and tyrannical regime, ‘India is broken’ – the title of a disturbing new book by the economic historian Ashoka Mody.

The number of Indians who sleep hungry rose from 190 million in 2018 to 350 million in 2022, and malnutrition and malnourishment killed nearly two-thirds of the children who died under the age of five last year. At the same time, Modi’s cronies have flourished. The Economist estimates that the share of billionaire wealth in India derived from cronyism has risen from 29 per cent to 43 per cent in six years. According to a recent Oxfam report, India’s richest 1 per cent owned more than 40.5 per cent of its total wealth in 2021 – a statistic that the notorious oligarchies of Russia and Latin America never came close to matching. The new Indian plutocracy owes its swift ascent to Modi, and he has audaciously clarified the quid pro quo. Under the ‘electoral bond’ scheme he introduced in 2017, any business or special interest group can give unlimited sums of money to his party while keeping the transaction hidden from public scrutiny.

Modi also ensures his hegemony by forging a public sphere in which sycophancy is rewarded and dissent harshly punished. Adani last year took over NDTV, a television news channel that had displayed a rare immunity to hate speech, fake news and conspiracy theories. Human Rights Watch has detailed a broad onslaught on democratic rights: ‘the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government used abusive and discriminatory policies to repress Muslims and other minorities’ and ‘arrested activists, journalists and other critics of the government on politically motivated criminal charges, including of terrorism’. Last month, as the BJP’s official spokesperson denounced the BBC as ‘the most corrupt organisation in the world’, tax officials launched a sixty-hour raid on the broadcaster’s Indian offices in apparent retaliation for a two-part documentary on Modi’s role in anti-Muslim violence.

Also last month, the opposition leader Rahul Gandhi was expelled from parliament to put a stop to his persistent questions about Modi’s relationship with Adani. Such actions are at last provoking closer international scrutiny of what Modi calls the ‘mother of democracy’, though they haven’t come as a shock to those who have long known about Modi’s lifelong allegiance to Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an organisation that was explicitly inspired by European fascist movements and culpable in the assassination of Mohandas Gandhi in 1948.

Why Prof. Ashoka Mody Believes India is Broken | Princeton International

https://international.princeton.edu/news/why-prof-ashoka-mody-believes-india-broken

I have long felt that that upbeat story is completely divorced from the lived reality of the vast majority of Indians. I wanted to write a book about that lived reality, about jobs, education, healthcare, the cities Indians live in, the justice system they encounter, the air they breathe, the water they drink. And when you look at India through that lens of that reality, the progress is halting at best and far removed from the aspirations of people and what might have been. India is broken in the sense that for hundreds of millions of Indians, jobs are hard to get, and education and health care are poor. The justice system is coercive and brutal. The air quality remains extraordinarily poor. The rivers are dying. And it's not clear that things are going to get better. Underlying that brokenness, social norms and public accountability have eroded to a point where India seems to be in a catch-22: Unaccountable politicians do not impose accountability on themselves; therefore, no one has an incentive to impose accountability for policy priorities that might benefit large numbers of people. The elite are happy in their gated first-world communities. They shrug their shoulders and say, “What exactly is the problem?”

———

Prof Ashoka Mody interviewed by Barkha Dutt

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8SEmML71KQ

Standard of Living by Country | Quality of Life by Country 2023

Numbeo Quality of Life

https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/standard-of-living-by-country

Finland 178.5

Oman 168.82

Japan 164.06

US 163.6

UK 156.94

UAE 156.94

Morocco 105.04

China 103.16

India 103

Pakistan 102.15

Russia 97.91

Egypt 87.21

Kenya 76.92

Bangladesh 64.54

Iran 63.6

Nigeria 54.71

#Indian couple beheaded themselves with homemade guillotine in ritual sacrifice, police in #India say. Hemubhai Makwana & his wife Hansaben both died by decapitation after using a homemade bladed mechanism on their farm in the #Gujarat.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/india-couple-behead-themselves-homemade-guillotine-hindu-ritual-human-sacrifice/ via @CBSNews

New Delhi — An Indian couple has allegedly died by suicide by using a guillotine-like mechanism to decapitate themselves in a sacrificial ritual, police said Sunday.

Hemubhai Makwana, 38, and his wife Hansaben, 35, both died by decapitation after using a homemade bladed mechanism in a hut on their farm in the western state of Gujarat, police said.

"The couple first prepared a fire altar before putting their heads under a guillotine-like mechanism held by a rope," Indrajeetsinh Jadeja, a police sub-inspector, was quoted as saying by Indian news outlets. "As soon as they released the rope, an iron blade fell on them, severing their heads, which rolled into the fire."

Fire is considered sacred in Hinduism and it plays a significant role in several worship rituals. The couple apparently designed the device used in their beheading in such a way that their heads would roll into the fire altar, completing their sacrificial ritual.

Police, who said they had found a suicide note addressed to family members, have launched an investigation. The couple is survived by two children and their parents.

The incident took place sometime between Saturday night and Sunday afternoon, when police were alerted.

Family members reportedly told police that the pair had offered prayers in the hut every day for the last year.

Ritual human sacrifices are not unknown in India, where official data show there were more than 100 reported cases between 2014 and 2021. But almost all known cases of human sacrifice involve people killing others to please gods, rather than themselves.

Earlier this month, Indian police arrested five men for murdering a woman in 2019 inside a Hindu temple in Guwahati, in what they said was a case of ritual human sacrifice.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/28/india-revolutions-economy-growth-future/

India: What the smartphone market tells us about its economy - BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-65491090

According to research firm the International Data Corporation (IDC), 31m smartphones were shipped in India during the first three months of this year.

That was 16% lower than in the same period of 2022 and the lowest first-quarter shipments in four years.

IDC highlighted that the sluggish demand came amid an uncertain economic outlook and as stockpiles of handsets remain high.

It also said that India's overall smartphone market will be flat this year after three quarters in a row of falling sales.

At the same time some analysts have pointed to the growing trend of "premiumisation" - when wealthier consumers move towards more expensive products.

"The premium segment's share almost doubled" in the first three months of this year compared to a year ago, according to Prachir Singh from technology market research firm Counterpoint.

However, as brands like Apple and Samsung benefit from this trend, demand for cheaper handsets made by companies like China's Xiaomi and Realme has been hit by the tough economic environment.

That end of the market is suffering as users take longer to upgrade their handsets, experts say.

The stark contrast between Apple's fortunes and the shrinking market for cheaper devices also reflects an uneven post-pandemic recovery in Asia's third largest economy.

"The K-shaped recovery is not allowing the consumption demand to become broad-based nor helping the wage growth especially of the population belonging to the lower half of the income pyramid," India Ratings and Research said.

"As a result, while there is visible demand for high-end automobiles, mobile phones and other luxury items, demand for items of mass consumption is still subdued," it added.

For example, sales of entry-level scooters were down by almost 20% in April this year, compared to the same month in 2019, before the pandemic hit.

This indicates that lower income customers "were are still hesitant to upgrade," according Manish Raj Singhania, the president of the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations.

It also reflects the on-going problems in India's rural economy, which have been worsened by extreme weather events.

Lack of demand in rural areas has also been driving the decline in the consumer goods, like snacks and fizzy drinks, where growth has dropped to single figures after a year and a half of double-digit increases.

Household spending on goods and services, which had grown 20% year on year in March 2022, has also slowed sharply this year.

That came as India's consumers have been squeezed by rising interest rates and stubbornly high inflation.

Overall, the country's economic growth slowed to 4.1% for the first three months of 2023, the lowest growth for a year, official figures show.

Unemployment in India

https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/27/economy/india-economic-miracle-issues-youth-intl-hnk-dst

High #Unemployment in #India: While people under the age of 25 account for more than 40% of India’s population, almost half of them – 45.8% – were unemployed as of December 2022. #Modi #BJP #economy #poverty #hunger Hindutva #Islamophobia

Too few jobs, too many workers and ‘no plan B’: The time bomb hidden in India’s ‘economic miracle’

Sunil Kumar knows all about working hard to achieve a dream. The 28-year-old from India’s Haryana state already has two degrees – a bachelor’s and a master’s – and is working on a third, all with a view to landing a well-paid job in one of the world’s fastest growing economies.

“I studied so that I can be successful in life,” he said. “When you work hard, you should be able to get a job.”

Kumar does now have a job, but it’s not the one he studied for – and definitely not the one he dreamed about.

He has spent the past five years sweeping the floors of a school in his village, a full-time job he supplements with a less lucrative side hustle tutoring younger students. All told, he makes about $85 a month.

It’s not much, he concedes, especially as he needs to support two aging parents and a sister, but it is all he has. Ideally, he says, he’d work as a teacher and put his degrees to use. Instead, “I have to do manual labor just to be able to feed myself.”

Kumar’s situation is not unusual, but a predicament faced by millions of other young Indians. Youth unemployment in the country is climbing sharply, a development that risks undermining the new darling of the world economy at the very moment it was expected to really take off.

India’s newfound status as the world’s most populous nation had prompted hopes of a youthful new engine for the global economy just as China’s population begins to dwindle and age. Unlike China’s, India’s working age population is young, growing, and projected to hit a billion over the next decade – a vast pool of labor and consumption that one Biden administration official has called an “economic miracle.”

But for young Indians like Kumar, there’s a flip side to this so-called miracle: too few jobs and too much competition.

In contrast to China, where economists fear there won’t be enough workers to support the growing number of elderly, in India the concern is there aren’t enough jobs to support the growing number of workers.

While people under the age of 25 account for more than 40% of India’s population, almost half of them – 45.8% – were unemployed as of December 2022, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank headquartered in Mumbai, which publishes job data more regularly than the Indian government.

Some analysts have described the situation to CNN as a “time bomb”, warning of the potential for social unrest unless more employment can be created.

Kumar, like others in his position, knows all too well the frustrations that can build when work is scarce.

“I get very angry that I don’t have a successful job despite my qualifications and education,” he said. “I blame the government for this. It should give work to its people.”

The bad news for people like Kumar, and the Indian government, is that experts warn the problem will only get worse as the population grows and competition for jobs gets even tougher.

Kaushik Basu, an economics professor at Cornell University and former chief economic adviser for the Indian government, described India’s youth unemployment rate as “shockingly high.”

It’s been “climbing slowly for a long time, say for about 15 years it’s been on a slow climb but over the past seven, eight years it’s been a sharp climb,” he said.

“If that category of people do not find enough employment,” Basu added, “then what was meant to be an opportunity, the bulge in that demographic dividend, could become a huge challenge and problem for India.”

Vulnerable employment, total (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate) - Pakistan, India | Data

Bangladesh 54%

Pakistan 54%

India 74%

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.VULN.ZS?locations=PK-IN-BD

------------

Sandeep Manudhane

@sandeep_PT

Why the size of the economy means little

a simple analysis

1) We are often told that India is now a $3.5 trillion economy. It is growing fast too. Hence, we must be happy with this growth in size as it is the most visible sign of right direction. This is the Quantity is Good argument.

2) We are told that such growth can happen only if policies are right, and all engines of the GDP - consumption, exports, investment, govt. consumption - are doing their job well. We tend to believe it.

3) We are also told that unless GDP grows, how can Indians (on average) grow? Proof is given to us in the form of 'rising per capita incomes' of India. And we celebrate "India racing past the UK" in GDP terms, ignoring that the average Indian today is 20 times poorer than the average Britisher.

4) All this reasoning sounds sensible, logical, credible, and utterly worth reiterating. So we tend to think - good, GDP size on the whole matters the most.

5) Wrong. This is not how it works in real life.

6) It is wrong due to three major reasons

(a) Distribution effect

(b) Concentration of power effect

(c) Inter-generational wealth and income effect

7) First comes the distribution effect. Since 1991, the indisputable fact recorded by economists is that "rich have gotten richer, and poor steadily stagnant or poorer". Thomas Piketty recorded it so well he's almost never spoken in New India now! Thus, we have a super-rich tiny elite of 2-3% at the top, and a vast ocean of stagnant-income 70-80% down below. And this is not changing at all. Do not be fooled by rising nominal per capita figures - factor in inflation and boom! And remember - per capita is an average figure, and it conceals the concentration.

8) Second is the Concentration of power effect. RBI ex-deputy governor Viral Acharya wrote that just 5 big industrial groups - Tata, Birlas, Adanis, Ambanis, Mittals - now disproportionately own the economic assets of India, and directly contribute to inflation dynamics (via their pricing power). This concentration is rising dangerously each year for some time now, and all government policies are designed to push it even higher. Hence, a rising GDP size means they corner more and more and more of the incremental annual output. The per capita rises, but somehow magically people don't experience it in 'steadily improving lives'.

9) Third is the Inter-generational wealth and income effect. Ever wondered why more than 90% of India is working in unstructured, informal jobs, with near-zero social security? Ever wondered why rich families smoothly pass on 100% of their assets across generations while paying zero taxes? Ever wondered how taxes paid by the rich as a per cent of their incomes are not as high as those paid by you and me (normal citizens)? India has no inheritance tax, but has a hugely corporate-friendly tax regime with many policies tailor-made to augment their wealth. Trickle down is impossible in this system. But that was the spiel sold to us in 1991, and later, each year! There is no incentive for giant corporates (and rich folks) to generate more formal jobs, as an ocean of underpaid slaves is ready to slog their entire lives for them. Add to that automation, and now, AI systems!

SUMMARY

Sadly, as India's GDP grows in size, it means little for the masses because trickle-down is near zero. That is because new formal jobs aren't being generated at scale at all (which in itself is a big topic for analysis).

So, our Quantity of GDP is different from Quality of GDP.

https://twitter.com/sandeep_PT/status/1675421203152896001?s=20

Income of poorest fifth plunged 53% in 5 yrs; those at top surged | India News,The Indian Express

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/income-of-poorest-fifth-plunged-53-in-5-yrs-those-at-top-surged-7738426/

In a trend unprecedented since economic liberalisation, the annual income of the poorest 20% of Indian households, constantly rising since 1995, plunged 53% in the pandemic year 2020-21 from their levels in 2015-16. In the same five-year period, the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39% reflecting the sharp contrast Covid’s economic impact has had on the bottom of the pyramid and the top.

---------------

A new survey, which highlights the economic impact of the pandemic on Indian households, found that the income of the poorest 20 percent of the country declined by 53 percent in 2020-21 from that in 2015-16.

https://www.thequint.com/news/india/poor-in-india-lose-half-their-income-in-last-5-years-rich-got-richer-survey#read-more

The survey, conducted by the People's Research on India's Consumer Economy (PRICE), a Mumbai-based think tank, also shows that in contrast, the same period saw the annual household income of the richest 20 percent grow by 39 percent.

Conducted between April and October 2021, the survey covered 20,000 households in the first stage, and 42,000 households in the second stage. It spanned over 120 towns and 800 villages in 100 districts.

Income Erosion in All Households Except the Rich Ones

The survey indicated that while the poorest 20 percent households witnessed an income erosion of 53 percent, the lower-middle-class saw a 39-percent decline in household income. The income of the middle-class, meanwhile, reduced by 9 percent.

However, the upper-middle-class and richest households saw their incomes rise by 7 percent and 39 percent, respectively.

The survey also showed that the richest households, on an average, accumulated more income per household as well as pooled income in the past five years than any other five-year period since liberalisation.

While the richest 20 percent accounted for 50.2 percent of the total household income in 1995, the survey shows that their share jumped to 56.3 percent in 2021. In contrast, the share of the poorest 20 percent dropped from 5.9 percent to 3.3 percent in the same period.

While 90 percent of the poorest 20 percent in 2016 lived in rural India, the figure dropped to 70 percent in 2021. In urban areas as well, the share of the poorest 20 percent households went from 10 percent in 2016 to 30 percent in 2021.

"The data reflects that casual labourers, petty traders, household workers, among others, in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities got hit the most by the pandemic. During the survey, we also noticed that while in rural areas, people in the lower middle income category (Q2) moved to the middle income category (Q3), in the urban areas, the shift has been downwards, from Q3 to Q2. In fact, the rise in poverty level of the urban poor has pulled down the household income of the entire category," reported The Indian Express, quoting Rajesh Shukla, MD and CEO of PRICE.

Most Middle-Class Breadwinners Are Illiterate or Have Primary Schooling

The survey further shows that while a majority of the breadwinners in 'Rich India' (top 20 percent) have completed high-school education (60 percent, of which 40 percent are graduates and above), nearly half of 'Middle India' (60 percent) only have primary education.

As for the bottom 20 percent, 86 percent are either illiterate or just have primary education. Only 6 percent are graduates and above.

(With inputs from The Indian Express, ICE360 2021 Survey.)

(At The Quint, we are answerable only to our audience. Play an active role in shaping our journalism by becoming a member. Because the truth is worth it.)

In the absence of real data, India's stats are all being manufactured by BJP to win elections.

Postponing India’s census is terrible for the country

But it may suit Narendra Modi just fine

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/01/05/postponing-indias-census-is-terrible-for-the-country

Narendra Modi often overstates his achievements. For example, the Hindu-nationalist prime minister’s claim that all Indian villages have been electrified on his watch glosses over the definition: only public buildings and 10% of households need a connection for the village to count as such. And three years after Mr Modi declared India “open-defecation free”, millions of villagers are still purging al fresco. An absence of up-to-date census information makes it harder to check such inflated claims. It is also a disaster for the vast array of policymaking reliant on solid population and development data.

----------

Three years ago India’s government was scheduled to pose its citizens a long list of basic but important questions. How many people live in your house? What is it made of? Do you have a toilet? A car? An internet connection? The answers would refresh data from the country’s previous census in 2011, which, given India’s rapid development, were wildly out of date. Because of India’s covid-19 lockdown, however, the questions were never asked.

Almost three years later, and though India has officially left the pandemic behind, there has been no attempt to reschedule the decennial census. It may not happen until after parliamentary elections in 2024, or at all. Opposition politicians and development experts smell a rat.

----------

For a while policymakers can tide themselves over with estimates, but eventually these need to be corrected with accurate numbers. “Right now we’re relying on data from the 2011 census, but we know our results will be off by a lot because things have changed so much since then,” says Pronab Sen, a former chairman of the National Statistical Commission who works on the household-consumption survey. And bad data lead to bad policy. A study in 2020 estimated that some 100m people may have missed out on food aid to which they were entitled because the distribution system uses decade-old numbers.

Similarly, it is important to know how many children live in an area before building schools and hiring teachers. The educational misfiring caused by the absence of such knowledge is particularly acute in fast-growing cities such as Delhi or Bangalore, says Narayanan Unni, who is advising the government on the census. “We basically don’t know how many people live in these places now, so proper planning for public services is really hard.”

The home ministry, which is in charge of the census, continues to blame its postponement on the pandemic, most recently in response to a parliamentary question on December 13th. It said the delay would continue “until further orders”, giving no time-frame for a resumption of data-gathering. Many statisticians and social scientists are mystified by this explanation: it is over a year since India resumed holding elections and other big political events.

The gates of Sulemanki Headworks were opened, closing them could have worsened the situation in Punjab. Pakistan Friendly Hand; Punjab Under Flood Condition | Pak Open Sulemanki head Works India Pakistan Border

https://india.postsen.com/local/806198.html

Sulemani Headworks built on Sutlej River in Pakistan.

Pakistan has extended a hand of friendship amidst the flood situation in India. The country which used to close the gates of its headworks and dams in the event of floods in Punjab, has opened the gates of Sulemanki headworks this year. This step taken by Pakistan has brought a big relief. In the past, 1.92 lakh cusecs of water reached the neighboring country from Hussainiwala.

In the last 6 days, floods have caused a lot of destruction in Punjab. While the situation has worsened in the eastern case, it is now being felt in western Malwa as well due to the release of water from the Harike headworks. Initially Pakistan had closed its gates of Sulemanki Headworks near Fazilka, but now water is flowing smoothly into Pakistani territory.

Water level in Harike crossed 2.14 lakh cusecs

With this step taken by Pakistan, the major threat of flood in Fazilka has been averted for the time being. In the past, 2.14 lakh cusecs of water was seen flowing in Harike of Sutlej. At the same time, the flow of water near Hussainiwala was recorded at 1.92 lakh cusecs, which is flowing towards Pakistan.

One-tenth of India's population escaped poverty in 5 years - government report

By Manoj Kumar

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/one-tenth-indias-population-escaped-poverty-5-years-government-report-2023-07-17/

NEW DELHI, July 17 (Reuters) - Nearly 135 million people, around 10% of India's population, escaped poverty in the five years to March 2021, a government report found on Monday.

Rural areas saw the strongest fall in poverty, according to the study, which used the United Nations' Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), based on 12 indicators such as malnutrition, education and sanitation. If people are deprived in three or more areas, they are identified as "MPI poor."

"Improvements in nutrition, years of schooling, sanitation and cooking fuel played a significant role in bringing down poverty," said Suman Bery, vice-chairman of the NITI Aayog, the government think-tank that released the report.

The percentage of the population living in poverty fell to 15% in 2019-21 from 25% in 2015/16, according to the report, which was based on the 2019-21 National Family Health Survey.

A report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) released last week said the number of people living in multidimensional poverty fell to 16.4% of India's population in 2021 from 55% in 2005.

According to UNDP estimates, the number of people, who lived below the $2.15 per day poverty line had declined to 10% in India in 2021.

India's federal government offers free food grain to about 800 million people, about 57% of country's 1.4 billion population, while states spend billions of dollars on subsidising education, health, electricity and other services.

The state that saw the largest number moving out of poverty was Uttar Pradesh, with 343 million people, followed by the states of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, according to the report.

Reporting by Manoj Kumar; Editing by Conor Humphries

Bhavika Kapoor ✋

@BhavikaKapoor5

𝑷𝒓𝒐𝒑𝒂𝒈𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒂:

- 5th largest economy 🚩

- 5 trillon economy 🐄

𝑻𝒓𝒖𝒕𝒉:

𝗜𝗻𝗱𝗶𝗮'𝘀 𝗦𝗲𝗰𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗚𝗗𝗣 𝘁𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗲 𝗖𝗼𝗻𝘀𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗹𝘆 𝗣𝗲𝗿𝗳𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗱 𝗣𝗼𝗼𝗿𝗹𝘆 𝗦𝗶𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝟮𝟬𝟭𝟰:

𝗠𝗮𝗻𝘂𝗳𝗮𝗰𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗴: The manufacturing sector has grown at an average rate of just 3.5% per year since 2014. This is well below the average growth rate of average 6% for the overall economy. The slow growth of the manufacturing sector is a major concern, as it is a key driver of job creation and economic growth. Poor performance of manufacturing in GDP is one of the major reasons of massive unemployment in India

𝗜𝗻𝗳𝗿𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗿𝘂𝗰𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗲: The infrastructure sector has also performed poorly in recent years. The growth rate of the infrastructure sector has averaged just 2% per year since 2014. This is below the average growth rate of 6% for the overall economy. The slow growth of the infrastructure sector is a major constraint on economic growth, as it limits the ability of businesses to expand and create jobs.

𝗔𝗴𝗿𝗶𝗰𝘂𝗹𝘁𝘂𝗿𝗲: The agriculture sector has also performed poorly in recent years. The growth rate of the agriculture sector has averaged just 2% per year since 2014. This is below the average growth rate of 6% for the overall economy. The slow growth of the agriculture sector is a major concern, as it is a key source of livelihood for millions of Indians.

𝗖𝗼𝗻𝘀𝘁𝗿𝘂𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻:

The construction sector has grown at an average rate of just 2.5% per year since 2014. This is well below the average growth rate of 6% for the overall economy. The slow growth of the construction sector is a major concern, as it is a key driver of job creation (as it gives employment to unskilled workforce too) and economic growth.

𝗕𝗮𝗻𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗙𝗶𝗻𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗦𝗲𝗿𝘃𝗶𝗰𝗲𝘀:

India's banking and financial services sector has faced a multitude of challenges, primarily in the form of non-performing assets (NPAs) and the resulting stress on bank balance sheets. The burden of NPAs, coupled with regulatory issues, limited credit availability, and risk-averse lending practices, has impacted the sector's ability to fuel economic growth. Additionally, the sector has witnessed instances of fraud and mismanagement, eroding investor confidence.

𝗣𝗼𝘄𝗲𝗿 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗘𝗻𝗲𝗿𝗴𝘆:

Despite efforts to improve power generation and distribution, India's power and energy sector has struggled to keep pace with the growing demand. Issues like inadequate infrastructure, transmission losses, fuel supply constraints, and pricing challenges have hampered the sector's progress. The heavy reliance on fossil fuels has also posed environmental challenges, requiring a shift towards cleaner and renewable energy sources.

In summary, addressing the above highlighted issues will require a comprehensive approach, involving policy reforms, infrastructure development, skill enhancement, and investment in research and development. However, I don't think Modi government has the talent, vision and political willingness to handle such complex issues.

https://twitter.com/BhavikaKapoor5/status/1680910458742767616?s=20

To Understand India’s Economy, Look Beyond the Spectacular Growth Numbers - The Wall Street Journal.

https://www.wsj.com/world/india/to-understand-indias-economy-look-beyond-the-spectacular-growth-numbers-31f5dd11

But the way India calculates its gross domestic product can at times overstate the strength of growth, in part by underestimating the weakness in its massive informal economy. There are also other indicators, such as private consumption and investment, that are pointing to soft spots. Despite cuts to corporate taxes, companies don’t appear to be spending on expansions.

-------------

BENGALURU, India—India is set to be the world’s fastest-growing major economy this year, but economists say the country’s headline growth numbers don’t tell the whole story.

The South Asian nation’s gross domestic product grew at more than 8% in its fiscal year ended in March compared with the previous year, driven by public spending on infrastructure, services growth, and an uptick in manufacturing. That would put India well ahead of China, which is growing at about 5%, and on track to hit Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s goal of becoming a developed nation by 2047.

But the way India calculates its gross domestic product can at times overstate the strength of growth, in part by underestimating the weakness in its massive informal economy. There are also other indicators, such as private consumption and investment, that are pointing to soft spots. Despite cuts to corporate taxes, companies don’t appear to be spending on expansions.

“If people were optimistic about the economy, they would invest more and consume more, neither of which is really happening,” said Arvind Subramanian, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and former chief economic adviser to the Modi government.

Private consumption, the biggest contributor to GDP, grew at 4% for the year, still slower than pre-pandemic levels. What’s more, economists say, it could have been even weaker if the government hadn’t continued its extensive food-subsidy program that began during the pandemic.

The problem is driven in part by how India emerged from the pandemic. Big businesses and people who are employed in India’s formal economy are generally doing well, but most Indians are in the informal sector or agriculture, and many of them lost work.

While India’s official data last year put unemployment at around 3%, economists also closely track data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a private economic research firm. It put unemployment at 8% for the year ended March.

At a small tea-and-cigarette stall in the southern city of Bengaluru, 55-year-old Ratnamma said many of her customers in the neighborhood, which once bustled with tech professionals and blue-collar workers, have moved out of the city and returned to rural villages. Some have come back, but she has fewer customers than she once did.

“Where did everyone go?” she said.

She makes about $12 a day in sales, she said, compared with as much as $100 on a good day in the past. It isn’t enough to cover her living expenses or repay a business loan she took out six months ago.

Economists say that the informal sector has been through three shocks in a decade—a 2016 policy aimed at tax evasion called “demonetization” that wiped out 90% of the value of India’s paper currency, a tax overhaul the following year that created more paperwork and expenses for small businesses, and the pandemic.

Pakistani YouTubers And Praise India Movement in Pakistan - India Today

"Indians love people from abroad lauding their achievements, but seem to derive the biggest satisfaction when Pakistanis gush over India's success. Pakistanis have understood that and have tapped into that, creating an entire industry of YouTubers in Pakistan"

https://www.indiatoday.in/sunday-special/story/praise-india-movement-pakistan-reaction-videos-on-indian-cricket-food-politics-youtube-shorts-pakistani-youtubers-2553682-2024-06-16

-------

There is a Praise India Movement in Pakistan if one goes by the pro-India videos being churned out by Pakistani YouTubers. If some are praising India's space programme, others are talking about its economic and political successes. Why are Pakistanis creating such YouTube videos, and that too, in such huge numbers?

"India did a big favour to Pakistan. It was also a tight slap for those Pakistanis who said India would deliberately lose to the USA to get Pakistan out of the T20 World Cup tournament. India is the world's number one team, and can never lose to the US," a man in a black salwar kameez states emphatically, looking at the camera. The person isn't an Indian gushing at India's victory over the USA in a T20 World Cup match, but a Pakistani speaking to a popular Pakistani YouTuber at a market in Pakistan.

The video by YouTuber Shaila Khan on her channel Naila Pakistani Reaction has over 3 lakh views in a day.

Indians love people from abroad lauding their achievements, but seem to derive the biggest satisfaction when Pakistanis gush over India's success. Pakistanis have understood that and have tapped into that, creating an entire industry of YouTubers in Pakistan.

There are 5,500 channels and over 84,000 videos just with the hashtag pakistanireactiononindia on YouTube. The number of channels, tracked by IndiaToday.In since November 2023, has grown by 1,000 in a matter of six months. Over 5,000 videos have been added under this hashtag since November.

We are talking about just one hashtag. There are several others with India-related content, some of which every Indian would have come across while scrolling through shorts and videos on YouTube.

This content boom by Pakistani YouTubers has sparked a Praise India Movement in Pakistan.

Seeing is believing, especially if it is about YouTube.

So, just try keying in #Pakistani on the YouTube search bar. The first few results are Pakistani Reaction, Pakistani Reaction on India and Pakistani Public Reaction -- all to do with content related to India.

Such is the rage that even #PakistaniDrama, one of Pakistan's biggest cultural exports, trends below the #PakistaniReaction.

WHAT ARE THE PRO-INDIA VIDEOS PAKISTANIS ARE CREATING

There was a flood of videos by Pakistani YouTubers lauding Team India right after their victory over the USA.

Though cricket is one of the favourites, the range of 'praise India' videos spans from India's economic might to infrastructural developments; from gastronomic delights to space programmes. Then there are videos of Pakistanis describing in amazement their wonderful discoveries during their first visit to India.

You name it, and they have it. There are Pakistani reaction clips to every Top 10 video, featuring India's shopping malls, highways, airports, college campuses, cars, bikes and even golgappas.

To understand the relative happiness scores, you have to understand that the Indian economy is enriching a few at the expense of the vast majority of Indians.

Pakistan has a huge informal economy that creates lots of jobs and income that are not accounted for in the headline GDP numbers.

On the other hand, Modi has killed India's informal economy on which hundreds of millions of Indians depended for their livelihoods.

Read this from the Wall Street Journal:

To Understand India’s Economy, Look Beyond the Spectacular Growth Numbers - The Wall Street Journal.

https://www.wsj.com/world/india/to-understand-indias-economy-look-beyond-the-spectacular-growth-numbers-31f5dd11