The global population increased by one billion over the last 12 years to reach 8 billion this year, according to the United Nations. Pakistan contributed 49 million people to the last billion, making it the fourth largest contributor after India (177 million), China (73 million) and Nigeria (51 million). Nigeria is expected to soon overtake Indonesia and Pakistan to become the world's 4th most populous nation. More than half of the projected increase in the global population up to 2050 will be concentrated in eight countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and the United Republic of Tanzania. Rising working age population is turning Pakistan into a major global consumer market. It is also fueling Pakistan's growing surplus labor exports and record overseas worker remittances.

| |

|

|

| World Population Visualization in 2022. Source: Visual Capitalist |

World's 7th Largest Consumer Market:

Pakistan's share of the working age population (15-64 years) is growing as the country's birth rate declines, a phenomenon called demographic dividend. With its rising population of this working age group, Pakistan is projected by the World Economic Forum to become the world's 7th largest consumer market by 2030. Nearly 60 million Pakistanis will join the consumer class (consumers spending more than $11 per day) to raise the country's consumer market rank from 15 to 7 by 2030. WEF forecasts the world's top 10 consumer markets of 2030 to be as follows: China, India, the United States, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, Pakistan, Japan, Egypt and Mexico. Global investors chasing bigger returns will almost certainly shift more of their attention and money to the biggest movers among the top 10 consumer markets, including Pakistan. Already, the year 2021 has been a banner year for investments in Pakistani technology startups.

|

| Consumer Markets in 2030. Source: WEF |

|

| World Population in 2050. Source: Visual Capitalist |

Labor Exports:

With rapidly aging populations and declining number of working age people in North America, Europe and East Asia, the demand for workers will increasingly be met by major labor exporting nations like Bangladesh, China, India, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia and Vietnam. Among these nations, Pakistan is the only major labor exporting country where the working age population is still rising.

|

| Working Age Population Declining Among Major Labor Exporters. Source: Nikkei Asia |

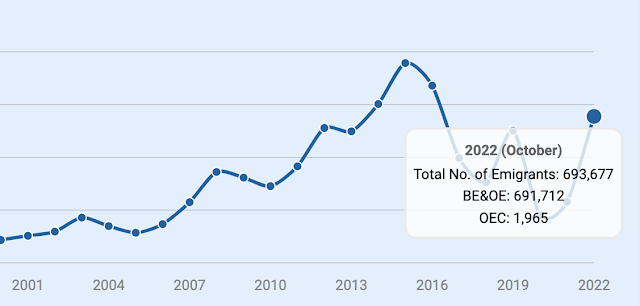

Over 10 million Pakistanis are currently working/living overseas, according to the Bureau of Emigration. Before the COVID19 pandemic hit in 2020, more than 600,000 Pakistanis left the country to work overseas in 2019. Nearly 700,000 Pakistanis have already migrated in this calendar year as of October, 2022. The average yearly outflow of Pakistani workers to OECD countries (mainly UK and US) and the Middle East was over half a million in the last decade.

|

| Pakistani Workers Going Overseas. Source: Bureau of Emigration |

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan is the 7th Largest Source of Migrants in OECD Nations

Pakistani-Americans: Young, Well-educated and Prosperous

Last Decade Saw 16.5 Million Pakistanis Migrate Overseas

Pakistan Remittance Soar 30X Since Year 2000

Pakistan's Growing Human Capital

Two Million Pakistanis Entering Job Market Every Year

Pakistan Projected to Be 7th Largest Consumer Market By 2030

Hindu Population Growth Rate in Pakistan

Do South Asian Slums Offer Hope?

Since the population of your taller than mountain friend is now declining, in the next billion India gets Gold, Pak gets Silver. Presumably Nigeria gets Bronze.

ReplyDeleteMigration Can Boost South Asia’s Recovery and Support Long-Term Development

ReplyDeletehttps://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/11/07/migration-can-boost-south-asia-s-recovery-and-support-long-term-development

Migration drives economic growth as it allows people to move to where they are more productive. International migrants from Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka who work in the Gulf states, for example, earn up to five times what they would at home and help generate some of the largest remittance inflows in the world. Nepal derives an estimated 20 percent of its income from remittance inflows, and in Bangladesh and Pakistan, remittance revenue accounts for 6 and 8 percent of GDP, respectively. Migration also allows people to adjust to local economic shocks, such as extreme-weather disasters, to which South Asia’s rural poor are highly vulnerable.

“While migration has numerous economic benefits, the costs of moving such as credit constraints, lack of information, and labor market frictions prevent them from being fully realized,” said Eaknarayan Aryal, Secretary, Ministry of Labor, Employment, and Social Security in Nepal. “Nepal and countries across South Asia must work to facilitate labor mobility as doing so is vital to the region’s recovery and resilience to future shocks.”

Poor South Asian migrants, many of whom hold temporary jobs in the informal sector, face several challenges such as precarious labor market conditions, visas tied to employment, and limited access to social protection. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed their long-standing vulnerabilities as they were disproportionately affected by restrictions to movement. However, the later phase of the pandemic has highlighted the crucial role migration can play in facilitating recovery. Survey data from the report suggests that in late 2021 and early 2022, migration flows are associated with movement from areas hit hard by the pandemic to those that were not, thus helping equilibrate demand and supply of labor in the aftermath of the COVID-19 shock. In Nepal, by late 2021, migrants were 13 percentage points more likely to be employed than those who did not migrate after facing job loss during the early months of the pandemic.

“Migration is picking up again in South Asia, but remains slow and uneven, raising concerns that the pandemic shock has had long-term impacts on the costs and frictions associated with it,” said Hans Timmer, World Bank Chief Economist for South Asia. “Policymakers must address these often-prohibitive costs and frictions and incorporate measures to de-risk migration.”

The report offers several recommendations on cutting the high costs of migration, including drawing bilateral and multilateral agreements, strengthening the remittance infrastructure, and offering information and training programs to help potential migrants make better decisions about moving. It also offers recommendations on de-risking migration through means such as more flexible visa policies, mechanisms to support migrant workers during shocks, and social protection programs.

“South Asia is the largest beneficiary of remittance in the world. Remittance has played a central role in alleviating poverty, coping with economic shocks, and making substantial progress toward sustainable development goals in Nepal,” said Dr. Biswash Gauchan, IIDS Executive Chair. “However, the socioeconomic and political cost of migration is also very high in the country where a substantial number of the working-age population has gone abroad in search of employment. IIDS is happy to host this regional conference on this crucial theme in Nepal in collaboration with the World Bank, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19.”

The next wave of mass migration

ReplyDeleteFEDERICA SAINI FASANOTTI

Extreme weather events are likely to become the main cause behind waves of immigration toward Europe.

https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/climate-migration/

urricane Ian, which disrupted the lives of millions when it swept over the Gulf of Mexico in late September this year, will not soon be forgotten. Torrential rains and winds of up to 240 kilometers per hour produced an extraordinary surge that flooded not only coastal areas but also their hinterland.

At the same time, Typhoon Noru was slamming into the Philippines. Earlier this year, Hurricane Fiona formed near Puerto Rico and hit Canada with unprecedented force, and Typhoon Nanmadol drove 9 million people to evacuate from their homes in Japan. Typhoon Merbok devastated Alaska with waves more than 50 feet high. Pakistan saw dramatic floods, aggravated by melting local glaciers. Leaving as much as one third of the country underwater, and more than 1,600 people and 800,000 livestock dead, the disaster will change the face of Pakistan for decades. The United Nations has called these phenomena the footprint of climate change.

Although Africa’s 54 states have not contributed significantly to the global emissions that accelerated climate change, the continent is one of the hardest hit. Desertification, dust storms and rising sea levels are poised to wreak havoc on large segments of the African populace.

By 2100, Africa is expected to account for 40 percent of the global population, which will grow to 11 billion. There will likely be 2.5 billion Africans by 2050. Amar Bhattacharya of the Brookings Institution writes that this growth will require an extraordinary increase in investment in “three critical areas: energy transitions and related investments in sustainable infrastructure; investments in climate change adaptation and resilience; and restoration of natural capital (through agriculture, food and land use practices) and biodiversity. … Altogether, Africa will need to invest around $200 billion per year by 2025 and close to $400 billion per year by 2030 on these priorities.”

African governments will be the first line of defense to safeguard the continent’s biological heritage, such as the rainforest of the Congo River Basin, which like the Amazon is crucial to removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Africa’s worst climate-related changes in recent decades are not hurricanes, but rather a persistent drought. The near extinction of Lake Chad is a prime example, as are the widening of the Sahel desert belt southward and the increasingly long periods without rain throughout the Maghreb. The population will grow but rainfall will decrease, thus rapidly shrinking the amount of arable land. And temperatures will rise – in a continent where only half of the 1.2 billion residents have access to electricity.

If these trends continue unchecked, much of Africa will ultimately become uninhabitable. In the Lake Chad basin, 5.3 million people (mostly fishermen and farmers) were displaced by climate-related changes. Experts predict that Africa’s glaciers will disappear: those of Mount Kenya by 2030 and those of Mount Kilimanjaro by 2040.

Already, small rural communities in the Maghreb struggle to produce enough to subsist. The same goes for intensive agriculture, which in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, generates up to a fifth of gross domestic product. Even slight disruptions will have exponential effects on those societies.

Remittances as an economic and social engine

ReplyDeleteby José Cabral, Managing Director, Ria Money Transfer

https://ibsintelligence.com/blogs/remittances-as-an-economic-and-social-engine/

The role remittances play in developing local economies through increased cash flows goes hand-in-hand with the social benefit they provide to the families and communities that receive them. The billions of dollars sent annually to developing countries can allow recipients to improve their standard of living through education, healthcare, food security, and savings. By giving people simplified access to finance by digital means, people across the world can achieve greater financial independence.

----------

For many of us, the ease of accessing digital financial services, such as contactless payments and electronic transactions, is often taken for granted. However, across many parts of the world, millions of people do not have access to digital bank accounts or credit and debit cards and rely instead on cash for daily transactions and savings.

In the age of globalisation and interconnectedness, more people than ever before are migrating to different countries in search of better opportunities. Many of the more than 280 million migrants around the world send money to loved ones back home. These cross-border transactions, called remittances, accounted for over $600 billion in income globally in 2021 and serve as a lifeline for many. Families receiving remittances invest them in education, healthcare, and food security.

The UK as a major remittance hotspot

Some countries around the world are hotspots for both immigration and remittances, as the two often go hand-in-hand. In the UK, over 14% of the country’s population in 2021 was foreign-born, totalling over 9.6 million people and a large portion of the job force. The majority hail either from other countries in Europe or from Asian countries such as India and Pakistan. With a significant migrant population comes a significant international cash flow; the UK is the source of billions of dollars in remittances sent annually, which make a sizeable impact on many recipient countries’ GDPs.

India is the country of origin for the largest portion of migrants in the UK, representing 9% of the country’s foreign-born population. It is also a leading recipient of remittances worldwide, and nearly 15% of UK remittances go to India. In 2020, India received over $3.9 billion in remittances from the UK alone, totalling almost 7% of all remittances sent to India in that year — only the US and the UAE had higher figures.

Nigeria receives the greatest total volume of remittances from the UK. An estimated $4.1 billion in remittances was sent from the UK to Nigeria in 2021, totalling 24% of all remittances sent to Nigeria that year. Other significant remittance flows from the UK include Pakistan, where almost 5% of the UK’s foreign-born population comes from and which received over $1.68 billion in remittances from the UK in 2020, and Poland, a country of origin to 7% of migrants in the UK and recipient of $1.14 billion in 2020.

The impact this has on economies

Remittance flows to the developing world have a powerful role in shaping local economies. Both Nigeria and India are global powerhouses with enormous economies, of which 4% and 3% respectively are derived from remittances. In Pakistan, remittances represent 8.7% of GDP, and over 6% of those remittances come from the UK. Cross-border money transfers to these regions are vital to the families who use this money to pay for food, medicine, and education, as well as to fund small businesses and make investments.

Fueled by rapid growth in Africa, global population hits 8 billion

ReplyDeleteAs the global population pushes 8 billion people, Africa and Asia are leading the growth. Nigeria could soon become the world’s fourth most populated country, while India is expected to overtake China as the world’s most populous country next year.

By Dan Ikpoyi and Chinedu Asadu Associated Press

November 15, 2022

|

LAGOS, NIGERIA

https://www.csmonitor.com/World/2022/1115/Fueled-by-rapid-growth-in-Africa-global-population-hits-8-billion

Among them is Nigeria, where resources are already stretched to the limit. More than 15 million people in Lagos compete for everything from electricity to light their homes to spots on crowded buses, often for two-hour commutes each way in this sprawling megacity. Some Nigerian children set off for school as early as 5 a.m.

And over the next three decades, the West African nation’s population is expected to soar even more: from 216 million this year to 375 million, the U.N. says. That will make Nigeria the fourth-most populous country in the world after India, China, and the United States.

----

The upward trend threatens to leave even more people in developing countries further behind, as governments struggle to provide enough classrooms and jobs for a rapidly growing number of youth, and food insecurity becomes an even more urgent problem.

Nigeria is among eight countries the U.N. says will account for more than half the world’s population growth between now and 2050 – along with fellow African nations Congo, Ethiopia, and Tanzania.

“The population in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to double between 2022 and 2050, putting additional pressure on already strained resources and challenging policies aimed to reduce poverty and inequalities,” the U.N. report said.

It projected the world’s population will reach around 8.5 billion in 2030, 9.7 billion in 2050, and 10.4 billion in 2100.

Other countries rounding out the list with the fastest growing populations are Egypt, Pakistan, the Philippines, and India, which is set to overtake China as the world’s most populous nation next year.

In Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, where more than 12 million people live, many families struggle to find affordable housing and pay school fees. While elementary pupils attend for free, older children’s chances depend on their parents’ incomes.

“My children took turns” going to school, said Luc Kyungu, a Kinshasa truck driver who has six children. “Two studied while others waited because of money. If I didn’t have so many children, they would have finished their studies on time.”

Rapid population growth also means more people vying for scarce water resources and leaves more families facing hunger as climate change increasingly impacts crop production in many parts of the world.

“There is also a greater pressure on the environment, increasing the challenges to food security that is also compounded by climate change,” said Dr. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India. “Reducing inequality while focusing on adapting and mitigating climate change should be where our policy makers’ focus should be.”

Still, experts say the bigger threat to the environment is consumption, which is highest in developed countries not undergoing big population increases.

“Global evidence shows that a small portion of the world’s people use most of the Earth’s resources and produce most of its greenhouse gas emissions,” said Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the Population Foundation of India. “Over the past 25 years, the richest 10% of the global population has been responsible for more than half of all carbon emissions.”

According to the U.N., the population in sub-Saharan Africa is growing at 2.5% per year – more than three times the global average. Some of that can be attributed to people living longer, but family size remains the driving factor. Women in sub-Saharan Africa on average have 4.6 births, twice the current global average of 2.3.

Remittances to Reach $630 billion in 2022 with Record Flows into Ukraine

ReplyDeletehttps://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/05/11/remittances-to-reach-630-billion-in-2022-with-record-flows-into-ukraine

WASHINGTON, May 11, 2022 — Officially recorded remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are expected to increase by 4.2 percent this year to reach $630 billion. This follows an almost record recovery of 8.6 percent in 2021, according to the World Bank’s latest Migration and Development Brief released today.

-----------

Remittances to South Asia grew 6.9 percent to $157 billion in 2021. Though large numbers of South Asian migrants returned to home countries as the pandemic broke out in early 2020, the availability of vaccines and opening of Gulf Cooperation Council economies enabled a gradual return to host countries in 2021, supporting larger remittance flows. Better economic performance in the United States was also a major contributor to the growth in 2021. Remittance flows to India and Pakistan grew by 8 percent and 20 percent, respectively. In 2022, growth in remittance inflows is expected to slow to 4.4 percent. Remittances are the dominant source of foreign exchange for the region, with receipts more than three times the level of FDI in 2021. South Asia has the lowest average remittance cost of any world region at 4.3 percent, though this is still higher than the SDG target of 3 percent.

-------

Top 10 remittance receiving nation: India, China, Mexico, The Philippines,Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Germany and Nigeria.

https://www.worldremit.com/en/blog/money-transfer/top-10-remittance-recipients/

India will become the world’s most populous country in 2023

ReplyDeleteChina is now suffering from a demographic slump

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/14/india-will-become-the-worlds-most-populous-country-in-2023?fbclid=IwAR2OTr5fDF1RfNbxMdAvsaOWr-g4cd8_P25_d0E8WV1zwii2qe_VMCepQ6w

China has been the world’s most populous country for hundreds of years. In 1750 it had an estimated 225m people, more than a quarter of the world’s total. India, not then a politically unified country, had roughly 200m, which ranked it second. In 2023 it will seize the crown. The un guesses that India’s population will surpass that of China on April 14th. India’s population on the following day is projected to be 1,425,775,850.

The crown itself has little value, but it is a signal of things that matter. That India does not have a permanent seat on the un Security Council while China does will come to seem more anomalous. Although China’s economy is nearly six times larger, India’s growing population will help it catch up. India is expected to provide more than a sixth of the increase of the world’s population of working age (15-64) between now and 2050.

China’s population, by contrast, is poised for a steep decline. The number of Chinese of working age peaked a decade ago. By 2050 the country’s median age will be 51, 12 years higher than now. An older China will have to work harder to maintain its political and economic clout.

Both countries took draconian measures in the 20th century to limit the growth of their populations. A famine in 1959-61 caused by China’s “great leap forward” was a big factor in persuading the Communist Party of the need to rein in population growth. A decade later China launched a “later, longer, fewer” campaign—later marriages, longer gaps between children and fewer of them. That had a bigger effect than the more famous one-child policy, introduced in 1980, says Tim Dyson, a British demographer. The decline in fertility, from more than six babies per woman in the late 1960s to fewer than three by the late 1970s, was the swiftest in history for any big population, he says.

It paid dividends. China’s economic miracle was in part the result of the rising ratio of working-age adults to children and oldsters from the 1970s to the early 2000s. With fewer mouths to feed, parents could invest more in each child than they otherwise would have. But having more parents than children, an advantage when the children are young, is a drawback as the parents age. The country will now pay a price as the economic-boomer generation retires and becomes dependent on the smaller generation following behind it.

India’s attempt to reduce fertility was less successful. It was the first country to introduce family planning on a national scale in the 1950s. Mass-sterilisation campaigns, encouraged by Western donors, grew and were implemented more forcefully during the state of emergency declared by Indira Gandhi, the prime minister, in 1975-77. Under the direction of her son Sanjay, the government forced men into vasectomy camps on pain of having their salaries docked or losing their jobs. Policemen nabbed poor men for sterilisation from railway stations. Around 2,000 men died from bungled procedures.

India will become the world’s most populous country in 2023

ReplyDeleteChina is now suffering from a demographic slump

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/14/india-will-become-the-worlds-most-populous-country-in-2023?fbclid=IwAR2OTr5fDF1RfNbxMdAvsaOWr-g4cd8_P25_d0E8WV1zwii2qe_VMCepQ6w

Forced sterilisations ended after Indira Gandhi lost an election. Though brutal, the campaign was not thorough enough to cause a dramatic drop in India’s birth rate. India’s fertility has dropped, but by less, and more slowly than China’s. With a median age of 28 and a growing working-age population, India now has a chance to reap its own demographic dividend. Its economy recently displaced Britain’s as the world’s fifth-biggest and will rank third by 2029, predicts State Bank of India. But India’s prosperity depends on the productivity of its youthful people, which is not as high as in China. Fewer than half of adult Indians are in the workforce, compared with two-thirds in China. Chinese aged 25 and older have on average 1.5 years more schooling than Indians of the same age.

That will not spare China from suffering the consequences of the demographic slump it engineered. The government ended the one-child policy in 2016 and removed all restrictions on family size in 2021. But birth rates have kept falling. China’s zero-covid policy has made young adults even more reluctant to bear children. The government faces resistance to its plans to raise the average retirement age, which at 54 is among the lowest in the world. The main pension fund may run out of money by 2035. Yet perhaps most painful for China will be the emergence of India as a superpower on its doorstep.

India will become the world’s most populous country in 2023

ReplyDeleteChina is now suffering from a demographic slump

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/14/india-will-become-the-worlds-most-populous-country-in-2023?fbclid=IwAR2OTr5fDF1RfNbxMdAvsaOWr-g4cd8_P25_d0E8WV1zwii2qe_VMCepQ6w

China has been the world’s most populous country for hundreds of years. In 1750 it had an estimated 225m people, more than a quarter of the world’s total. India, not then a politically unified country, had roughly 200m, which ranked it second. In 2023 it will seize the crown. The un guesses that India’s population will surpass that of China on April 14th. India’s population on the following day is projected to be 1,425,775,850.

The crown itself has little value, but it is a signal of things that matter. That India does not have a permanent seat on the un Security Council while China does will come to seem more anomalous. Although China’s economy is nearly six times larger, India’s growing population will help it catch up. India is expected to provide more than a sixth of the increase of the world’s population of working age (15-64) between now and 2050.

China’s population, by contrast, is poised for a steep decline. The number of Chinese of working age peaked a decade ago. By 2050 the country’s median age will be 51, 12 years higher than now. An older China will have to work harder to maintain its political and economic clout.

Both countries took draconian measures in the 20th century to limit the growth of their populations. A famine in 1959-61 caused by China’s “great leap forward” was a big factor in persuading the Communist Party of the need to rein in population growth. A decade later China launched a “later, longer, fewer” campaign—later marriages, longer gaps between children and fewer of them. That had a bigger effect than the more famous one-child policy, introduced in 1980, says Tim Dyson, a British demographer. The decline in fertility, from more than six babies per woman in the late 1960s to fewer than three by the late 1970s, was the swiftest in history for any big population, he says.

It paid dividends. China’s economic miracle was in part the result of the rising ratio of working-age adults to children and oldsters from the 1970s to the early 2000s. With fewer mouths to feed, parents could invest more in each child than they otherwise would have. But having more parents than children, an advantage when the children are young, is a drawback as the parents age. The country will now pay a price as the economic-boomer generation retires and becomes dependent on the smaller generation following behind it.

India’s attempt to reduce fertility was less successful. It was the first country to introduce family planning on a national scale in the 1950s. Mass-sterilisation campaigns, encouraged by Western donors, grew and were implemented more forcefully during the state of emergency declared by Indira Gandhi, the prime minister, in 1975-77. Under the direction of her son Sanjay, the government forced men into vasectomy camps on pain of having their salaries docked or losing their jobs. Policemen nabbed poor men for sterilisation from railway stations. Around 2,000 men died from bungled procedures.

India will become the world’s most populous country in 2023

ReplyDeleteChina is now suffering from a demographic slump

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2022/11/14/india-will-become-the-worlds-most-populous-country-in-2023?fbclid=IwAR2OTr5fDF1RfNbxMdAvsaOWr-g4cd8_P25_d0E8WV1zwii2qe_VMCepQ6w

Forced sterilisations ended after Indira Gandhi lost an election. Though brutal, the campaign was not thorough enough to cause a dramatic drop in India’s birth rate. India’s fertility has dropped, but by less, and more slowly than China’s. With a median age of 28 and a growing working-age population, India now has a chance to reap its own demographic dividend. Its economy recently displaced Britain’s as the world’s fifth-biggest and will rank third by 2029, predicts State Bank of India. But India’s prosperity depends on the productivity of its youthful people, which is not as high as in China. Fewer than half of adult Indians are in the workforce, compared with two-thirds in China. Chinese aged 25 and older have on average 1.5 years more schooling than Indians of the same age.

That will not spare China from suffering the consequences of the demographic slump it engineered. The government ended the one-child policy in 2016 and removed all restrictions on family size in 2021. But birth rates have kept falling. China’s zero-covid policy has made young adults even more reluctant to bear children. The government faces resistance to its plans to raise the average retirement age, which at 54 is among the lowest in the world. The main pension fund may run out of money by 2035. Yet perhaps most painful for China will be the emergence of India as a superpower on its doorstep.

Will Pakistan be able to weaponize its population, the way Africa is doing? Going to Middle east is not an option, given that welcome drink won't be the there. Without stability and education, high numbers are a burden

ReplyDeleteZen: "Going to Middle east is not an option..."

ReplyDeleteThere was a dip in Pakistani worker migration due to COVID in the last couple year. However, the numbers have picked up again with nearly 700,000 Pakistanis going to work overseas as of October this year.

https://beoe.gov.pk/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=b1b4890b1c9705af3b244646c1cd140ad59f0f8a-1577426531-0-Aa7RUMV3c8t-qhTE_wsuXG88GqpOS3SMabeKgwCnn8PO1ZJYBDvkMO4w6yBOsrXLO6HMNxdolaCf201abOoKQn8NU4gXnLVBmFUbaSSfa4KACGuXEphZ-Wpph8DHxEtVFtH_nr3GpKtP5CCKSEDnMfnNes7Xq-dXpcOlCoO6icVLUUltg12JbgVKSxVgUZ7CtIDNT7WC6AqKIYyGIhk-uLlsnW0VYaWhYjeRDqqTPExfqB_E1oGyko049nDUaiNxQL7JRYlKIkcGUVzYTraqiok

Overseas migration of Pakistanis is also diversifying, with an increasing number of migrants going to America and Europe. This is reflected in remittance sources. EU countries are now the fastest growing source of remittances to Pakistan.

https://www.riazhaq.com/2022/05/european-union-fastest-growing-source.html

The data shows that a lot more of the migrants are now skilled labor while the share of unskilled migrants is declining.

Here's an ILO report excerpt:

"Pakistani migrant workers were skilled

(42%) and involved in semi-skilled jobs such as welders, secretaries, masons, carpenters, plumbers and so

on. Another proportion of the labour migration was composed of unskilled labourers (39%) such as

agriculturists, labourers or farmers. Projections about future trends indicate that the number of Pakistani

labour migrants will continue rising to reach 15.5 million in 2020 (Government of Pakistan, 2018"

https://migration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Pakistan%20Migration%20Snapshot%20Final.pdf

PAKISTAN MIGRATION SNAPSHOT AUGUST 2019

ReplyDelete"While migration to Pakistan has a strong cross-border dimension, the main destination countries of the large Pakistani diaspora are scattered across the world. In 2017, 22 per cent of the 6 million Pakistani emigrants lived in Saudi Arabia, 18 per cent in India, 16 per cent in the United Arab Emirates, 15 per cent in Europe and 6 per cent in the United States of America (Figure 3)"

https://migration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Pakistan%20Migration%20Snapshot%20Final.pdf

PAKISTAN MIGRATION SNAPSHOT

ReplyDeleteAUGUST 2019

https://migration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Pakistan%20Migration%20Snapshot%20Final.pdf

Table 1: Pakistan Key demographic indicators

Indicator Pakistan

Total area, in sq km, million 0.796

Population (2017), thousand d 197,016

Migrant population (2017), thousand d 3,398

Migrant population (2017), % total population d 1.7%

Urban Population (2017), % of total b 36.4%

Population Growth rate (2017), annual % b 1.9%

Human Development Index (2017) c 0.562

Country Rank out of 189 c 150/189

Unemployment (2017), % of labour force c 4.0%

Youth Unemployment (2017), % ages 15-24 c 7.7%

Multidimensional Poverty Headcount (2015), % 38.8%

Gini Coefficient (2010-2017)

c 30.7

Foreign Direct Investment (net inflows, 2017), current USD, billion b 2.815

Net Official Development Assistance Received (2017), current USD, billion b 2.953

Personal Remittances Received (2017), current USD, billion b 19.698

Personal Remittances Received (2017), % GDP b 6.5%

Source: b World Bank, 2018; c UNDP, 2018; d UNDESA, 2017;

e UNDP and OPHI (2016).

What was Pakistan's Private Consumption Expenditure in 2022?

ReplyDeletePakistan Private Consumption Expenditure was reported at 324.824 USD bn in Dec 2022. This records an increase from the previous number of 290.625 USD bn for Dec 2021. See the table below for more data.

https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/pakistan/private-consumption-expenditure

Pakistan Private Consumption Expenditure was reported at 324.824 USD bn in Dec 2022. This records an increase from the previous number of 290.625 USD bn for Dec 2021.

Pakistan Private Consumption Expenditure data is updated yearly, averaging 31.179 USD bn from Dec 1960 to 2022, with 63 observations.

The data reached an all-time high of 324.824 USD bn in 2022 and a record low of 3.084 USD bn in 1960.

Pakistan Private Consumption Expenditure data remains in an active status in CEIC and is reported by CEIC Data.

The data is categorized under World Trend Plus’s Global Economic Monitor – Table: Nominal GDP: Private Consumption Expenditure: USD: Annual: Asia.

CEIC shifts year-end for annual Private Consumption Expenditure and converts it into USD. Private Consumption Expenditure is calculated as the sum of Household and NPISHs consumption. The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics provides Private Consumption Expenditure in local currency based on SNA 2008 with benchmark year 2015-2016. The State Bank of Pakistan average market exchange rate is used for currency conversions. Private Consumption Expenditure is reported in annual frequency, ending in June of each year. Private Consumption Expenditure prior to 2016 is based on SNA 2008 with benchmark year 2005-2006. Private Consumption Expenditure prior to 2000 is sourced from the World Bank.

In mid-April, India is forecast to surpass China as the world's most populous country.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63957562

The Asian giants already have more than 1.4 billion people each, and for over 70 years have accounted for more than a third of the global population.

China's population is likely to begin shrinking next year. Last year, 10.6 million people were born, a little more than the number of deaths, thanks to a rapid drop in fertility rate. India's fertility rate has also fallen substantially in recent decades - from 5.7 births per woman in 1950 to two births per woman today - but the rate of decline has been slower.

So what does India overtaking China as the most populous country in the world mean?

China reduced its population growth rate by about half from 2% in 1973 to 1.1% in 1983.

Demographers say much of this was achieved by riding roughshod over human rights - two separate campaigns promoting just one child and then later marriages, longer gaps between children and fewer of them - in what was a predominantly rural and overwhelmingly uneducated and poor country,

India saw rapid population growth - almost 2% annually - for much of the second half of the last century. Over time, death rates fell, life expectancy rose and incomes went up. More people - especially those living in cities - accessed clean drinking water and modern sewerage. "Yet the birth rate remained high," says Tim Dyson, a demographer at the London School of Economics.

India launched a family planning programme in 1952 and laid out a national population policy for the first time only in 1976, around the time China was busy reducing its birth rate.

But forced sterilisations of millions of poor people in an overzealous family planning programme during the 1975 Emergency - when civil liberties were suspended - led to a social backlash against family planning. "Fertility decline would have been faster for India if the Emergency hadn't happened and if politicians had been more proactive. It also meant that all subsequent governments treaded cautiously when it came to family planning," Prof Dyson says.

East Asian countries such as Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand, which launched population programmes much later than India, achieved lower fertility levels, cut infant and maternal mortality rates, raised incomes and improved human development earlier than India.

India has added more than a billion people since Independence in 1947, and its population is expected to grow for another 40 years. But its population growth rate has been declining for decades now, and the country has defied dire predictions about a "demographic disaster".

So India having more people than China is no longer significant in a "concerning" way, say demographers.

Rising incomes and improved access to health and education have helped Indian women have fewer children than before, effectively flattening the growth curve. Fertility rates have dipped below replacement levels - two births per woman - in 17 out of 22 states and federally administered territories. (A replacement level is one at which new births are sufficient to maintain a steady population.)

The decline in birth rates has been faster in southern India than in the more populous north. "It is a pity that more of India could not have been like south India," says Prof Dyson. "All things being equal, rapid population growth in parts of north India have depressed living standards".

In mid-April, India is forecast to surpass China as the world's most populous country.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63957562

It could, for example, strengthen India's claim of getting a permanent seat in the UN Security Council, which has five permanent members, including China.

India is a founding member of the UN and has always insisted that its claim to a permanent seat is just. "I think you have certain claims on things [by being the country with largest population]," says John Wilmoth, director of the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

The way India's demography is changing is also significant, according to KS James of the Mumbai-based International Institute for Population Sciences.

Despite drawbacks, India deserves some credit for managing a "healthy demographic transition" by using family planning in a democracy which was both poor and largely uneducated, says Mr James. "Most countries did this after they had achieved higher literacy and living standards."

More good news. One in five people below 25 years in the world is from India and 47% of Indians are below the age of 25. Two-thirds of Indians were born after India liberalised its economy in the early 1990s. This group of young Indians have some unique characteristics, says Shruti Rajagopalan, an economist, in a new paper. "This generation of young Indians will be the largest consumer and labour source in the knowledge and network goods economy. Indians will be the largest pool of global talent," she says.

India needs to create enough jobs for its young working age population to reap a demographic dividend. But only 40% of of India's working-age population works or wants to work, according to Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE).

More women would need jobs as they spend less time in their working age giving birth and looking after children. The picture here is bleaker: only 10% of working-age women were participating in the labour force in October, according to CMIE, compared with 69% in China.

Then there's migration. Some 200 million Indians have migrated within the country - between states and districts - and their numbers are bound to grow. Most are workers who leave villages for cities to find work. "Our cities will grow as migration increases because of lack of jobs and low wages in villages. Can they provide migrants a reasonable living standard? Otherwise, we will end up with more slums and disease," says S Irudaya Rajan, a migration expert at Kerala's International Institute of Migration and Development.

Demographers say India also needs to stop child marriages, prevent early marriages and properly register births and deaths. A skewed sex ratio at birth - meaning more boys are born than girls - remains a worry. Political rhetoric about "population control" appears to be targeted at Muslims, the country's largest minority when, in reality, "gaps in childbearing between India's religious groups are generally much smaller than they used to be", according to a study from Pew Research Center.

And then there's the ageing of India

Demographers say the ageing of India receives little attention.

In 1947, India's median age was 21. A paltry 5% of people were above the age of 60. Today, the median age is over 28, and more than 10% of Indians are over 60 years. Southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu achieved replacement levels at least 20 years ago.

"As the working-age population declines, supporting an older population will become a growing burden on the government's resources," says Rukmini S, author of Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India.

"Family structures will have to be recast and elderly persons living alone will become an increasing source of concern," she says.

The year 2023 marks a historic turning point for Asia's demography: For the first time in the modern era, India is projected to surpass China as the most populous country.

ReplyDeletehttps://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Asia-Insight/Old-Japan-young-India-and-the-risks-of-a-world-of-8bn-people

Besides China (1.426 billion) and India (1.417 billion), five other Asian countries had over 100 million people as of 2022, the U.N. figures show. Indonesia had 276 million, Pakistan's population was at 236 million, Bangladesh counted 171 million, Japan had 124 million and the Philippines had 116 million. Vietnam, with 98 million, is expected to join the club soon.

------------

Even though economists expect India's gross domestic product to grow around 7% in 2023 -- the highest among major economies -- and although the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be over, India continues to face high unemployment rates of around 8%, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy, a local private researcher. That shows the country is not creating enough jobs to support the growing population.

---------

Kumagai also said that India's growing demand for food could be felt beyond its borders.

"The challenge for India concerning food is that the production of agricultural products is easily affected by the weather," he said. "On the other hand, domestic demand is increasing rapidly. As such, when production is low, domestic supply is prioritized, which eventually may lead to restrictions on exports, just as India restricted wheat exports in 2022, which could cause food problems in other countries as well."

--------

While the South Asian nation's growing and youthful population spells opportunities for development, it also creates layers of challenges, from poverty reduction to education. Experts say soaring demand for food could affect India's trade with other countries, while the World Bank recently estimated that India will need to invest $840 billion into urban infrastructure over the next 15 years to support its swelling citizenry.

"This is likely to put additional pressure on the already stretched urban infrastructure and services of Indian cities -- with more demand for clean drinking water, reliable power supply, efficient and safe road transport amongst others," the bank's report said.

India's dilemmas are only part of a complex and diverging Asian population picture -- split between young, growing countries and aging, declining ones. Humanity's latest milestone turns a spotlight on this gap and the problems on both sides of it.

---

Reaching a world of 8 billion people signals significant improvements in public health that have increased life expectancy, the U.N. said. But it also pointed out, "The world is more demographically diverse than ever before, with countries facing starkly different population trends ranging from growth to decline."

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Asia. The region has young countries with a median age in the 20s, such as India (27.9 years old), Pakistan (20.4) and the Philippines (24.7), as well as old economies with median ages in the 40s, including Japan (48.7) and South Korea (43.9). The gap between the young and the old has gradually widened over the past decades.

While India faces a lack of jobs and infrastructure to support its growing population, Japan faces a serious reduction in births, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which its government says is a "critical situation." Either way, the population trends are increasingly impacting economies and societies.

Even though economists expect India's gross domestic product to grow around 7% in 2023 -- the highest among major economies -- and although the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be over, India continues to face high unemployment rates of around 8%, according to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy, a local private researcher. That shows the country is not creating enough jobs to support the growing population.

India will soon overtake China as the world’s most populous country

ReplyDeleteBut it will struggle to reap the benefits of a young workforce

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/01/05/india-will-soon-overtake-china-as-the-worlds-most-populous-country

You might expect production to shift to labour-rich India. That is especially so as relations between China and the West become more hostile. But companies, especially in more advanced industries, tend to set up production in places where there are already suppliers and skilled workers. That is where India has a problem.

India’s development has relied less on industry than that of other emerging economies. Manufacturing generates 14% of Indian GDP, compared with 27% in China. What industry India does have clusters in the relatively prosperous south and west. But it is the poorer northern states that are making more babies (see map). Uttar Pradesh, for instance, is home to 17% of India’s population but has only 9% of its industrial jobs. That mismatch will hamper India’s economic growth.

Internal migration would help. Road, rail and air connections are improving. The government is investing massively in digitisation, which should encourage people to move by helping them to hold on to their ID cards, welfare benefits and voting rights and to communicate with their families at home.

Yet these efforts will take years, maybe decades, to pay dividends. Even as India’s population grows, it will struggle to capitalise on the potential of its young workforce.

Sadanand Dhume

ReplyDelete@dhume

Contrary to all the hype, India’s market for consumer goods remains very small. The Chinese buy about 8X more iPhones and nearly 100X more BMWs than Indians. Starbucks has 20X as many outlets in China as in India. [My take] v

@WSJopinion

https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-middle-class-free-trade-modi-tariffs-domestic-market-purchasing-power-cars-phones-protectionist-11672953530?st=u3cdwkybzdgefw2&reflink=share_mobilewebshare

https://twitter.com/dhume/status/1611155691540217858?s=20&t=FIhHrWvDf922ge89Kn5sKg

With his love for alliteration, Prime Minister Narendra Modi often talks India up by referring to its three Ds: democracy, demography and demand. They are supposed to “propel the nation to new heights of economic progress,” to quote one of his tweets. The slogan underscores a widely held belief in India on which Mr. Modi’s economic policy relies—that the country has a large market irresistible to foreign firms. Unfortunately, that isn’t true.

---

One can see how Mr. Modi and others came to believe in the myth of the massive Indian market. It’s easy to confuse the size of a country’s economy or population with the size of its domestic market. India’s gross domestic product of $3.2 trillion makes it the fifth largest in the world. This year India will overtake China to become the world’s most populous nation.

A population of 1.4 billion does indeed translate into a large market for some products. About 1.2 billion Indians own cellphones, of which half are smartphones. Facebook has 330 million users in India, nearly twice as many as in the U.S. India was the third-largest consumer of oil in 2021, behind America and China. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, India was the largest arms importer in the world between 2017 and 2021. India was the top weapons export market for Russia, France and Israel.

But the size of India’s consumer market has long been hyped. A widely cited 2007 McKinsey report giddily predicted that by 2025 “India will become a middle class country” with 583 million middle-class consumers. In 2017, Morgan Stanley said India’s 400 million millennials were “one of the world’s strongest sources of untapped economic potential.” It described them sitting “in Mumbai cafés, browsing social media accounts on their smartphones while occasionally shopping for new shoes online.”

Reality is much more drab. Though India has many potential consumers, they have very little purchasing power, economists Shoumitro Chatterjee and Arvind Subramanian wrote in a 2020 paper. Though the country’s population matches China’s, India’s “true market” is only about 15% to 20% as large. India represents only 1.5% to 5% of the global market.

The Pew Research Center estimates that only 66 million Indians—less than 5% of the population—have a middle-class daily income of between $10.01 and $20 in purchasing-power terms. In China, that number is 493 million, or 34.9% of the population. In short, the vaunted Indian middle class wields much slimmer wallets than its Chinese counterpart.

Take cars, a consumer good that’s emblematic of the middle class world-wide. In 2021 Chinese bought 26.3 million cars, more than seven times as many as the 3.7 million cars Indians purchased that year, by the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers’ estimate. For luxury brands like BMW, the Chinese market is nearly 100 times as large as India’s.

The number of Indians who can afford to watch movies on Netflix, FaceTime friends on an iPhone, or stop by a Starbucks for a cappuccino remains vanishingly small. Less than 3% of Netflix’s 223 million users are in India—despite the company’s charging them less than half what it does U.S. consumers. India’s vaunted cellphone market is dominated by inexpensive Chinese brands like Xiaomi. Indians bought fewer than six million iPhones in 2021. Chinese bought about 50 million. Starbucks operates more than 6,000 stores in China, but only about 300 in India.

Sadanand Dhume

ReplyDelete@dhume

Contrary to all the hype, India’s market for consumer goods remains very small. The Chinese buy about 8X more iPhones and nearly 100X more BMWs than Indians. Starbucks has 20X as many outlets in China as in India. [My take] v

@WSJopinion

https://www.wsj.com/articles/india-middle-class-free-trade-modi-tariffs-domestic-market-purchasing-power-cars-phones-protectionist-11672953530?st=u3cdwkybzdgefw2&reflink=share_mobilewebshare

https://twitter.com/dhume/status/1611155691540217858?s=20&t=FIhHrWvDf922ge89Kn5sKg

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

This column has set off a mini firestorm here, so let me quickly respond to some of the objections. First, people point out that obviously China is a larger market than India. After all, it’s a larger economy. Chinese GDP in 2021: $17.73T. Indian GDP: $3.18T. 1/n

https://twitter.com/dhume/status/1611369521146732553?s=20&t=FIhHrWvDf922ge89Kn5sKg

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

But this doesn’t refute my central point—that contrary to popular belief India’s market is small by global standards. We should ask how China pulled so far ahead. In 1990 Chinese GDP ($360b) was similar to Indian GDP ($321b). Now China’s economy is 5.6X larger than India’s. 2/n

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

Over the past decade, the gap between China and India has not shrunk. It has grown. In 2012, the Chinese economy was 4.7X larger than India’s. 3/n

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

Moreover, as I show in my piece, mere GDP figures are misleading. For many consumer goods, the gap between the Chinese market and the Indian market is LARGER than the gap between Chinese and Indian GDP. 4/n

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

Now to the second major objection: “Don’t talk about Starbucks, iPhones and Netflix subscriptions. These are luxury goods.” My response: The fact that they are luxury goods in India proves my point. If Indians had more disposable income they would not be seen as luxury goods. 5/n

Sadanand Dhume

@dhume

Or take cars, a middle class good in much of the world. In 2021, the Chinese bought 26.3m cars. Indians bought 3.7m cars. The Chairman of Maruti Suzuki recently pointed out that it could take 40 years for the Indian car market to catch up with China’s. 6/n

India will take 40 yrs to draw level with China's car penetration: Bhargava

As a result, the small car market has been shrinking as two-wheeler customers shelve or delay plans to upgrade to a four-wheeled drive

https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/india-to-take-191-yrs-to-reach-chinese-car-penetration-levels-r-c-bhargava-122122000775_1.html

Postponing India’s census is terrible for the country

ReplyDeleteBut it may suit Narendra Modi just fine

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/01/05/postponing-indias-census-is-terrible-for-the-country

Three years ago India’s government was scheduled to pose its citizens a long list of basic but important questions. How many people live in your house? What is it made of? Do you have a toilet? A car? An internet connection? The answers would refresh data from the country’s previous census in 2011, which, given India’s rapid development, were wildly out of date. Because of India’s covid-19 lockdown, however, the questions were never asked.

Almost three years later, and though India has officially left the pandemic behind, there has been no attempt to reschedule the decennial census. It may not happen until after parliamentary elections in 2024, or at all. Opposition politicians and development experts smell a rat.

Narendra Modi often overstates his achievements. For example, the Hindu-nationalist prime minister’s claim that all Indian villages have been electrified on his watch glosses over the definition: only public buildings and 10% of households need a connection for the village to count as such. And three years after Mr Modi declared India “open-defecation free”, millions of villagers are still purging al fresco. An absence of up-to-date census information makes it harder to check such inflated claims. It is also a disaster for the vast array of policymaking reliant on solid population and development data.

India’s first proper census was conducted in 1881 by British colonial administrators, who calculated that finding out more about their subjects would help them consolidate power. Independent India continued to hold one every decade. Census data are used to determine who gets food aid, how much is paid to schools and hospitals across the country, and how constituency boundaries are drawn. They also form the basis for more detailed, representative-sample surveys on household consumption, a key measure of poverty, and on social attitudes and access to health care, education and technology.

For a while policymakers can tide themselves over with estimates, but eventually these need to be corrected with accurate numbers. “Right now we’re relying on data from the 2011 census, but we know our results will be off by a lot because things have changed so much since then,” says Pronab Sen, a former chairman of the National Statistical Commission who works on the household-consumption survey. And bad data lead to bad policy. A study in 2020 estimated that some 100m people may have missed out on food aid to which they were entitled because the distribution system uses decade-old numbers.

Similarly, it is important to know how many children live in an area before building schools and hiring teachers. The educational misfiring caused by the absence of such knowledge is particularly acute in fast-growing cities such as Delhi or Bangalore, says Narayanan Unni, who is advising the government on the census. “We basically don’t know how many people live in these places now, so proper planning for public services is really hard.”

Postponing India’s census is terrible for the country

ReplyDeleteBut it may suit Narendra Modi just fine

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/01/05/postponing-indias-census-is-terrible-for-the-country

The home ministry, which is in charge of the census, continues to blame its postponement on the pandemic, most recently in response to a parliamentary question on December 13th. It said the delay would continue “until further orders”, giving no time-frame for a resumption of data-gathering. Many statisticians and social scientists are mystified by this explanation: it is over a year since India resumed holding elections and other big political events.

True, the census process requires training some 3m “enumerators” to go door to door with the questionnaires, and the government’s ambition to register the answers digitally for the first time may make the task more complex. Teachers, who usually do much of this work, have only just returned to schools. The window for conducting the census is short, as the monsoon makes much of the country difficult to get around for much of the year. Yet such logistical hurdles never stopped previous administrators undertaking the census. Mr Modi should explain why his government appears unable to follow their lead.■

Between 2000 and 2020, the number of migrants grew in 179 countries or areas. Germany, Spain, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and the United States of America gained the largest number of migrants during that period. By contrast, in 53 countries or areas, the number of international migrants declined between 2000 and 2020. Armenia, India, Pakistan, Ukraine and the United Republic of Tanzania were among the countries that experienced the most pronounced declines. In many cases, the declines resulted from the old age of the migrant populations or the return of refugees and asylum seekers to their countries of origin.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.un.org/en/desa/international-migration-2020-highlights

In 2020, Turkey hosted the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers worldwide (nearly 4 million), followed by Jordan (3 million), the State of Palestine (2 million) and Colombia (1.8 million).3 Other major destinations of refugees, asylum seekers or other persons displaced abroad were Germany, Lebanon, Pakistan, Sudan, Uganda and the United States of America.

In terms of regional migration corridors, Europe to Europe was the largest globally, with 44 million migrants in 2020, followed by the corridor Latin America and the Caribbean to Northern America, with nearly 26 million (figure 14). Between 2000 and 2020, some regional migration corridors grew very rapidly. The corridor Central and Southern Asia to Northern Africa and Western Asia grew the most, with 13 million migrants added between 2000 and 2020; more than tripling in size. The majority of that increase resulted from labour migration from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka to the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (Valenta, 2020). While it is too soon to understand the full extent, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 may have slowed the growth of this regional migration corridor. In many of the GCC countries, tens of thousands of migrant workers in the construction, hospitality, retail and transportation sectors lost their jobs due to the pandemic and were required to return home (UN-Habitat, 2020).

India’s diaspora, the largest in the world, is distributed across a number of major countries of destination, with the United Arab Emirates (3.5 million), the United States of America (2.7 million) and Saudi Arabia (2.5 million) hosting the largest numbers of migrants from India. Other countries hosting large numbers of migrants from India included Australia, Canada, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. China and the Russian Federation also have spatially diffused diasporas. In 2020, large numbers of migrants born in China were living in Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and the United States of America. Migrants from the Russian Federation were residing in several countries of destination, many of which are member states of the CISFTA, including Belarus, Kazakhstan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan, as well as Germany and the United States of America.

During the year 2022 (December), 832,339 Pakistanis proceeded abroad for the purpose of employment.

ReplyDeletehttps://beoe.gov.pk/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=b1b4890b1c9705af3b244646c1cd140ad59f0f8a-1577426531-0-Aa7RUMV3c8t-qhTE_wsuXG88GqpOS3SMabeKgwCnn8PO1ZJYBDvkMO4w6yBOsrXLO6HMNxdolaCf201abOoKQn8NU4gXnLVBmFUbaSSfa4KACGuXEphZ-Wpph8DHxEtVFtH_nr3GpKtP5CCKSEDnMfnNes7Xq-dXpcOlCoO6icVLUUltg12JbgVKSxVgUZ7CtIDNT7WC6AqKIYyGIhk-uLlsnW0VYaWhYjeRDqqTPExfqB_E1oGyko049nDUaiNxQL7JRYlKIkcGUVzYTraqiok

Since inception of the Bureau in the year 1971, more than 10 million emigrants have been provided overseas employment duly registered with the Bureau of Emigration & Overseas Employment. During the year 2015, highest number of Pakistanis(946,571) proceeded abroad for the purpose of employment. During the year 2022 (December), 832,339 Pakistanis proceeded abroad for the purpose of employment.

Digital census process continues smoothly: PBS

ReplyDeletehttps://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2023/03/16/digital-census-process-continues-smoothly-pbs/

ISLAMABAD: The process of the 7th Population and Housing Census, being conducting digitally for the first time in the country’s history, has been going on smoothly all across the country, the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) reported here on Thursday.

“The overall progress and speed of the census process is very encouraging and satisfactory,” PBS said in a press statement issued here.

The process includes an option for self-enumeration, which was made available from February 20, 2023, till March 10, 2023, and field operations of house listing and enumeration commenced from March 01, 2023, that will continue till April 4, 2023.

Conducting a census digitally ensures transparency, data-driven procedures, real-time monitoring of progress through geo-tagging using GIS systems, and wider acceptability of census results, said PBS press statement.

It said structures were listed from March 1st to March 10, 2023, during which all the residential and economic units were geotagged along with the classification of economic activities as per international standards.

It said, the self-enumeration portal was very well received by people who have enumerated themselves using the portal launched and this method was optional.

Currently, the final phase of the census i.e. enumeration is ongoing starting from March 12, 2023, and would continue till April 4, 2023. In this phase, the data about household members and their demographic characteristics, various Socio-Economic Indicators, as well as Housing characteristics, are being collected.

PBS technical team is analyzing and assessing the data and trends on a day-to-day basis to ensure the quality of the data and progress in identified 291 blocks all over Pakistan. Physical verification and digital monitoring are being used for quality assurance.

PBS has established 495 Census Support Centers (CSC) at the Census District level and 495 Census Support Centers (CSC) at the tehsil level where over 1,095 IT experts of NADRA and PBS team are available 24/7 for technical assistance and facilitation of field staff.

The control room has been established at the CSC level which facilitates census field staff during field operation and for this purpose, NADRA technical teams are available to redress all IT-related issues.

A call center is operating 24/7 for facilitation, assistance and suggestions through the toll-free number 0800-57574.

It said, certain quarters were spreading false and misinformation, adding information shared on the PBS website and official social media should be believed and considered.

Riaz Haq

ReplyDelete@haqsmusings

2021 was impacted by #Covid restrictions! Hence the low number for #Pakistan !! All middle income developing countries are now experiencing “brain drain” as the young middle class has the resources to travel for better available opportunities overseas.

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1661959642635960320?s=20

-------

Pakistan's brain drain crisis escalates as thousands leave

https://www.dw.com/en/pakistans-brain-drain-crisis-escalates-as-thousands-leave/a-65733569

By Zoya Nazir in Islamabad | Darko Janjevic

Many educated Pakistanis are looking to move abroad as living costs continue to climb and political unrest deepens in their home country.

Sana Hashim, who works at a digital marketing startup in Islamabad, is facing a dilemma: She wants to join thousands of highly qualified workers who have already moved out of Pakistan, but is worried about abandoning her family.

"I have applied to a few firms in the Middle East and received interview calls, too," the 29-year-old told DW. "But, even if I get a job, I can't just pack my bags and leave. Who is going to look after my aging parents?"

In 2021, about 225,000 Pakistanis left the country, but the number nearly tripled to 765,000 last year, according to the official numbers published by The Express Tribune daily.

The 2022 numbers include 92,000 of highly educated professionals such as doctors, engineers, information technology experts and accountants. Some of them go to the West, others to Middle Eastern countries such Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

And the trend shows no sign of abating in 2023. The latest data indicate that nearly 200,000 people left in the first three months of the year. Nasir Khan, an experienced immigration agent working in Islamabad, told DW that he has never seen such a surge before.

"It's not just the younger lot — people of all ages turn up to my office daily," he said. "They are so tired and frustrated; it literally seems they want to run away from here."

Salaries eaten by galloping inflation

IT specialist Nouman Shah told DW that he took the plunge and moved to Saudi Arabia last year because of the rising living costs in Pakistan.

"My low earnings were inadequate to run a household there, while a job prospect in Riyadh was too good to pass up," he said.

For years, people in Pakistan have had to contend with joblessness, low wages and limited prospects to advance their careers. Now, the country is also facing a deep political and economic crisis. In addition to the power struggle between the supporters of former Prime Minister Imran Khan and the current government led by Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif — a struggle that has repeatedly turned violent — the value of the Pakistani rupee has been plummeting, and the government is struggling to secure a loan from the International Monetary Fund. The cost of imports such as crude oil has also skyrocketed, stoking inflation.

According to JS Global Securities, inflation in the country is projected to reach over 37% year-on-year in May, the highest since July 1965.

"A salaried individual like myself is really struggling because prices have skyrocketed in recent months," Sana Hashim said. "My income hasn't increased, but the inflation has."

Crisis reaches students outside Pakistan

Fears of a deteriorating economic situation have also put Pakistanis studying abroad in distress. Formerly, international students would return to the country to work, but now, with fewer jobs available, many opt to stay in their host countries and apply for permanent residency.

Parents are also finding it more challenging to transfer money to their children who are enrolled in universities abroad, as a result of the devaluation of the Pakistani currency.

"My parents are having a harder time affording my education in Australia, but I hope the decision will pay off when I finally obtain an Australian passport," student Ujala Tariq said.

The UK has become one of the world’s most accepting places for foreign workers, according to a survey in 24 nations revealing a sharp increase in British acceptance of economic migration.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/feb/23/uk-now-among-most-accepting-countries-for-foreign-workers-survey-finds

Shortfall of 330,000 workers in UK due to Brexit, say thinktanks

Read more

People in the UK emerged as less likely to think that when jobs are scarce employers should give priority to people of their own country than those in Norway, Canada, France, Spain, the US, Australia and Japan. Only Germany and Sweden were more open on that question.

In what the study’s authors described as “an extraordinary shift”, only 29% of people in the UK in 2022 said priority over jobs should go to local people, compared with 65% when the same question was asked in 2009.

The findings come as employers call for more migration to help fill more than 1m vacancies, and after the prime minister appointed the anti-immigration firebrand Lee Anderson as deputy chair of the Conservative party. He has called people arriving in small boats on the south coast “criminals” and called for them to be “sent back the same day”. Police have been deployed to hotels where asylum seekers are being housed amid violent protests by anti-immigration activists.

“It was unthinkable a decade ago that the UK would top any international league table for positive views of immigration,” said Prof Bobby Duffy, the director of the Policy Institute at King’s College London, who shared the findings from the latest round of the survey exclusively with the Guardian and the BBC. “But that’s where we are now, with the UK the least likely, from a wide range of countries, to say we should place strict limits on immigration or prohibit it entirely.”

The UK ranked fourth out of 24 nations for the belief that immigrants have a very or quite good impact on the development of the country – ahead of Norway, Spain, the US and Sweden.

One factor in the shift in opinions on the question of “British jobs for British workers” may be that in 2009 the UK was in a deep recession, with more than double today’s unemployment, whereas today the economy suffers from a worker shortage, with 1.1m vacancies in the UK, 300,000 more than before the pandemic.

Robert Jenrick, the immigration minister, last year urged employers to look to the British workforce in the first instance and “get local people”, although the government has widened visa programmes for seasonal workers and care staff.

Duffy said the findings showed that “it’s time to listen more carefully to public attitudes”. He said: “Politicians often misread public opinion on immigration. In the 2000s, Labour government rhetoric and policy on this issue was more relaxed than public preferences, and arguably they paid the price – but the current government is falling into the reverse trap.”

People in the UK are now the least likely of the 24 countries that participate in the World Values Survey study to think immigration increases unemployment, and second from top in thinking that immigrants fill important job vacancies.

They are very likely to say immigration boosts cultural diversity, and very unlikely to think immigration comes with crime and safety risks. However, more people in the UK think immigration leads to “social conflict” than in several other countries, including Canada, Japan and China.

Why Americans Are Having Fewer Babies - WSJ

ReplyDeletehttps://www.wsj.com/articles/why-americans-are-having-fewer-babies-3be7f6a9

The number of babies born in the U.S. started plummeting 15 years ago and hasn’t recovered since. What looked at first like a temporary lull triggered by the 2008 financial crisis has stretched into a prolonged fertility downturn. Provisional monthly figures show that there were about 3.66 million babies born in the U.S. last year, a decline of 15% since 2007, even though there are 9% more women in their prime childbearing years.

The decline has demographers puzzled and economists worried. America’s longstanding geopolitical advantages, they say, are underpinned by a robust pool of young people. Without them, the U.S. economy will be weighed down by a worsening shortage of workers who can fill jobs and pay into programs like Social Security that care for the elderly. At the heart of the falling birthrate is a central question: Do American women simply want fewer children? Or are life circumstances impeding them from having the children that they desire?

---------

To maintain current population levels, the total fertility rate—a snapshot of the average number of babies women have over their lifetime—must stay at a “replacement rate” of 2.1 children per woman. In 2021, the U.S. rate was 1.66. Had fertility rates stayed at their 2007 peak, the U.S. would now have 9.6 million more kids, according to Kenneth Johnson, senior demographer at the University of New Hampshire.

Federal agencies are treating the slump like a temporary downturn. The Social Security Administration’s board of trustees projects that the total fertility rate will slowly climb to 2 by 2056 and hold there until the end of the century. Yet it’s been over a decade since fertility rates reached that level. Last year there were 2.8 workers for every Social Security recipient. That ratio is projected to shrink to 2.2 by 2045, roughly two-thirds what it was in 2000.

Some other developed countries are in a far deeper childbearing trough than the U.S. In South Korea, the total fertility rate hit a world record low of 0.84 in 2020 and has since sagged to 0.78. Italy’s rate slid to 1.24 last year. China’s population fell in 2022 for the first time in decades because its fertility rate has been far below the replacement rate for years. Its two-century reign as the world’s most populous country is expected to end this year when India overtakes it, if it hasn’t already.

In a recent note to clients, Neil Howe, a demographer at Hedgeye Risk Management, pointed to a World Bank report showing that the 2020s could be a second consecutive “lost decade” for global economic growth, in large part because of worsening demographics. By 2026 or 2027, he wrote, the growth rate of the working-age population in the entire high-income and emerging-market world will turn from slightly positive to slightly negative, reversing a durable driver of economic growth since the Industrial Revolution.

This shift will make the U.S. more dependent on immigration to supply enough workers to keep the economy humming. Immigrants accounted for 80% of U.S. population growth last year, census figures show, up from 35% just over a decade ago. Yet the number of young immigrant women coming to the U.S. has diminished, Johnson said, and the decline in fertility has been greatest among Hispanics.

Having fewer children has already changed the social fabric of the country’s schools, neighborhoods and churches. J.P. De Gance, president and founder of Communio, a nonprofit that helps churches encourage marriage, said that lower marriage and birth rates are one of the largest drivers of the decline in religious affiliation that’s left pews empty across the country. That matters for the whole community, De Gance said, because churches give lonely people a place to form friendships, as well as feeding hungry people and running schools that fill gaps in public education. “When that’s diminished, the entire culture’s diminished,” he said.